“Fraud is the daughter of greed.” - Jonathan Gash

Murder, fraud, and pre-flight checklists:

Fraud and violent crime have something in common. Both contain opportunity, motive, and offender rationalization. Once a fraud is revealed and the king’s (or queen’s) crown is gone, people gulp up every morsel. “How did this happen?” “How can I prevent it from happening to me?”

This is the brilliance behind true crime networks, shows, and podcasts. A big reason why people listen is to prevent their untimely death. I was an Investigation Discovery nut, but after a while realized there are only so many ways to die and so many motives. So too there are a finite number of ways to commit fraud.

Reading breathless coverage on why a crypto kingdom collapsed scratches the curiosity itch, and, on the margins, could help someone avoid similar fraudulent schemes. Rather than focusing on these takes, let’s take a step back and identify the core components of conning.

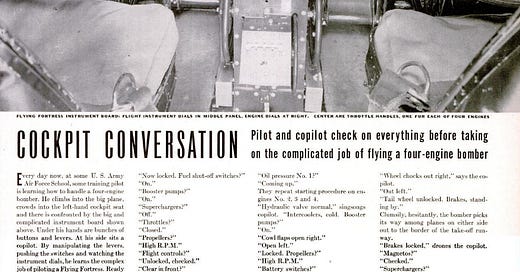

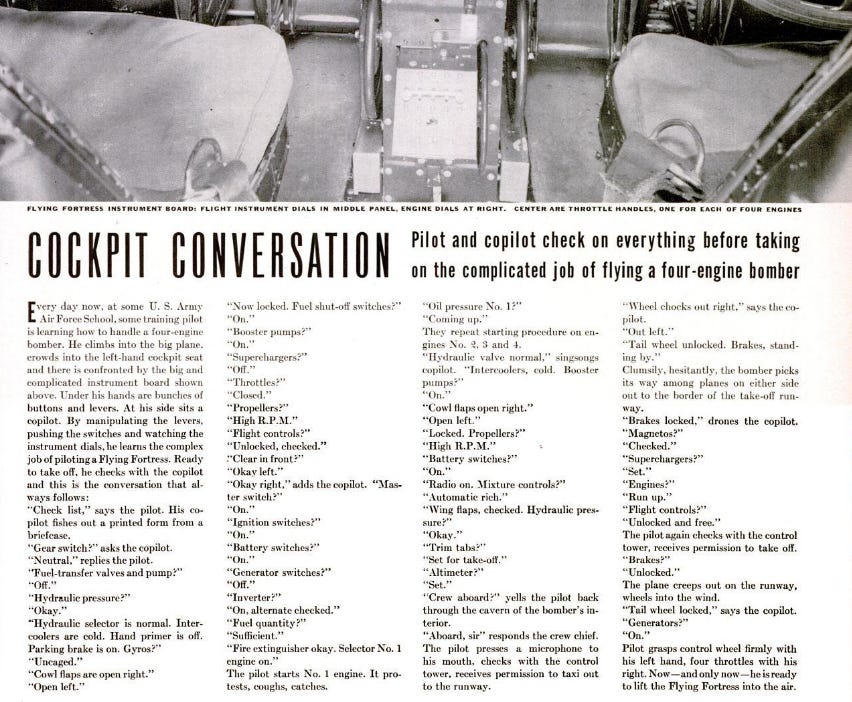

Looking at the anatomy of frauds can be compared to a pre-flight checklist. These checklists arose following the 1935 crash of a prototype Boeing B-17 (Model 299). The pilots had failed to release a simple, yet crucial locking mechanism.

Consider this post the inverse of a pre-flight safety check. Everything needs to be checked off by pilots to ensure safety. Here, the more boxes that are ticked, the higher percentage chance it’s a fraud. In a complex world, both assist in cutting through noise to focus on the essentials.

I hope this piece will help you become more well-informed on the recurring themes that run through frauds and avoid investing pitfalls. It is by no means exhaustive - think of it as a primer. As you’ll see, basic research and common sense would uncover many frauds.

I’m an accountant by training and have nearly a decade of experience in short only equity research. I’ve also had the privilege of learning from sharp short sellers like John Hempton.

What fraud is and is not:

The word fraud comes from the Latin fraus, meaning deceit or injury.

To prove fraud in the court of law, there must be a material statement made that is known to be false. Omission of important information equally applies. The other, innocent party does not know there was a misrepresentation and relies upon the statement. Lastly, damages occur.

In accountancy training, fraud is typically taught under a triangle framework. The three sides are the triangle are opportunity, motivation, and rationalization.

Opportunity is the “how it’s done”. Opportunity occurs via weak internal controls or poor culture which originates at the top. In other words, there is the ability to commit fraud due to organizational shortcomings.

Motivations are the person’s reason(s) for fraudulent action. It’s the “why” and can range from greed to personal financial issues. In the public markets, a myopic focus on short-termism leads to pressure to meet investor expectations and receive bonuses based on meeting certain financial metrics.

Rationalization is the justification – “I deserve this”. Or “This is temporary. I’ll pay it all back.”

The first known fraud occurred in 300 BCE. A Greek sea merchant named Hegestratos obtained an insurance policy (known as a bottomry) against his ship and cargo. However, there was no cargo onboard. He planned to sink the boat halfway through the voyage and collect the insurance proceeds. The crew somehow found out about Hegestratos’ plan to sacrifice them for insurance money (perhaps as he was trying to sink the ship) and he went overboard and drowned.

It’s important to differentiate between fraud and speculation. Speculating is high risk and involves buying something with the hope to sell it at a higher price later. Asset bubbles, which are formed by speculation, are not necessarily fraudulent. Bubbles form when the price of an object is extremely high compared to its actual value.

The Beanie Baby craze in the late 1990’s saw the prices for certain stuffed plush figures surge to hundreds or thousands of dollars. Higher prices were dependent on incremental buyers coming in and paying more money for a stuffed animal.

At some point, price exhaustion occurred and prices tumbled back to earth. Beanie Babies unwittingly helped me become a short seller, as I was caught up in the craze as a teenager and experienced the full boom and bust.

Herein, the focus will be on the softer fraudulent elements as opposed to concentrating on hard, numerical figures/corporate controls/accounting. Resources like Financial Shenanigans address the accounting games companies can play.

The human element is integral (and arguably the most interesting). Human behavior does not change. Look no further than the proficiency of fraudsters using the same tricks over and over since time immemorial.

Anatomy of a fraud:

Frauds are like history in that it never exactly repeats itself, but rhymes. Similar themes run through frauds. It’s a financial adviser’s fiduciary duty to be informed.

Key elements comprising a con job include:

The mark(s) – the duped who on some level, wants to believe in the impossible

The setup – how the con is facilitated

The trust factor – supposedly trustworthy parties short circuit due diligence

The instigator – the driving force

Frauds are systems: there’s elements, interconnections and a function/purpose. The building blocks are interrelated and feed upon each other with the ultimate purpose to make money.

The mark(s) – the duped who on some level, want to be believe in the impossible

On certain levels, those that are conned want to believe that something too good to be true happens to him/her. Complete naiveness on the part of the duped can occur, but is more uncommon.

This isn’t victim blaming – we all want to believe we are special; that we can be this lucky; and that we deserve this. It’s our inner child who believes if we find our prince we can live happily ever after.

Simon Leviev, better known as “The Tinder Swindler”, conned victims out of millions of dollars. He presented himself on Tinder as a Russian-Israeli diamond mogul Lev Leviev. At first he would charm matches with private jet flights and lavish gifts.

Soon after, he would tell them he was being targeted by his enemies, going so far as to send pictures of his bodyguard bloodied and bruised. With his life in danger, he desperately needed money.

Why would a rich diamond king need cash? He said he had to put a block on all his credit cards to remain safe. If the credit cards were swiped, his enemies would find him. The victims took out loans and collectively sent him $10 million.1

When asked about repayment, Simon sent forged documents showing fake bank transfers. These women wanted to believe that against all odds, this story was true, that they would at the very least be repaid and likely set up with Simon for life as his partner.

The setup – how the con is facilitated:

1) Easy money/fails the smell test:

The con is presented as an opportunity for easy money. If viewed absent of emotions, it would show itself too good to be true.

Like crypto investors who staked coins to earn a return far above what you could find anywhere else. This involves pledging coins to a cryptocurrency platform in exchange for more coins. Of course, the percentage return was based on how the coins performed. If they cratered, so too did the value of your coins, meaning your “safe” interest was vaporized along with the staked coins.

If crypto is too complicated (more on this later), consider Charles Ponzi, for whom the term Ponzi Scheme is named. He told investors he’d found a way to make a risk-free profit by buying Spanish mail coupons and redeeming them for U.S. stamps to take advantage of a weak Spanish currency. A return of 50% in 45 days was promised (compared to 5% interest rates from banks at that time). At one point, almost 75% of Boston’s police force had invested in the scheme.

In reality, Ponzi used new investor money to repay old investors. The scheme worked so long as new investors were coming into the fold. No one questioned the nuts and bolts of the idea – for example, realizing an arbitrage profit for 15,000 investors2 would have necessitated Titanic-sized ships to transport the postal coupons to the United States.

In reality, if these easy money, idealized opportunities truly existed they would have already been alpha’d away. They fail the smell test.

2) Red flags are pooh-poohed away:

Red flags are always present from the outset, ignored, and then become obvious in hindsight. These flags are signals to do more due diligence, as something doesn’t add up. Red flags denote a variance from baseline - what would be expected in a clean operation.

On the personal side of red flags, if you’re dating someone and every single ex is crazy, it’s a good chance he/she is the crazy one. It’s the same song, different verse if everyone someone encounters is a jerk.

In the case of FTX, which was at one time worth $32 billion, not having a board of directors is a factory of flags.

More generally, certain incorporation locations are suspect, like the state of Utah or Vancouver, Canada. Or having a no name auditor (or no auditor if you’re Tether). FTX and Madoff both employed unknown auditors.

The same holds true with corporate counsel – legitimate firms hire well-known firms that can be vetted.

Certain industries are replete with fraud, such as junior miners and biotech firms. Junior miners are mining companies in the development and exploration phase. They don’t have their own mining operation and are trying to prove their reserves, sucking up tons of capital in the process.

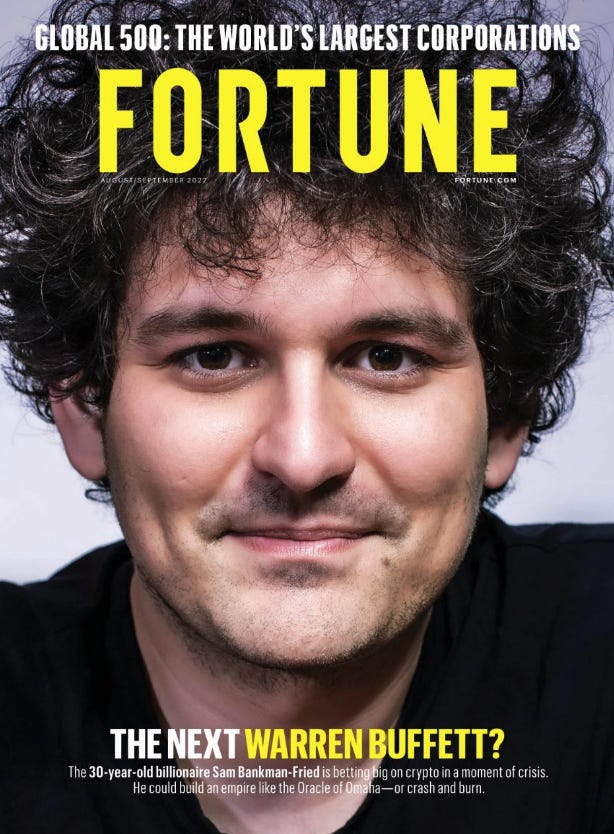

As an investor, do not take what management says at face value. Don’t make the mistake Ackman did with Valeant by initially believing CEO Michael Pearson’s denials that anything was awry. And definitely don’t proclaim any company to be the newest Berkshire Hathaway, as Ackman did with Valeant.

By the same token, it isn’t wise to crown someone the next Warren Buffett. Sam Bankman-Fried was proclaimed to be the next Buffett by Fortune magazine only a few months before his empire unraveled. As Justin Fox wrote, “the cases where you can be almost sure the ‘next Buffett’ curse will hold are ones where the resemblance is obviously only superficial”.

Others who have been declared as the next Buffett include the dethroned SPAC king Chamath Palihapitiya and Eddie Lampert Jr. If you want to lose money, Chamath’s SPACs were the perfect vehicles. Eddie Lampert Jr. stripped Sears/Kmart and made off like a robber baron. Heads they win, tails they win. You always lose.

Be curious about people who assume prominent roles in a large company yet do not have requisite experience. A prime example is someone who’s only experience in TV production yet becomes the head of a bank.

If smart people struggle to understand something, that’s a flag to do more work:

“I’ve played in the crypto market, I don’t understand it, I still don’t understand it.” he said. “Believe it or not, I made money and I still don’t know how I made money in crypto. I don’t know what crypto is.” - John Mack, Former CEO of Morgan Stanley

To date crypto has been a disappointment when looking at its widely-promoted promises. Instead of being a de-centralized mechanism putting more power in the hands of ordinary people, it’s extremely centralized. Last year, the WSJ reported that 0.01% of bitcoin holders controlled 27% of the currency in circulation. Compare this to the U.S., where the top 1% hold 33% of all wealth.

In the art world, a huge red flag is any painting that magically appears with questionable provenance3. The Salvator Mundi painting was supposedly a lost work of art by Leonardo da Vinci.

Two American art dealers bought the painting in an auction for $1,175. It eventually sold for $450 million. Scheduled to be put on exhibit at the Louvre, it was cancelled without explanation.

When rediscovered, the painting was in a poor state, and it appears that the art restorer took wide liberty in the restoration process, making it into something much different than was given to her.

"You have the old parts of the painting which are original—these are by pupils—and the new parts of the painting, which look like Leonardo, but they are by the restorer. In some part, it's a masterpiece by Dianne Modestini". - Frank Zöllner, da Vinci expert

3) Opaque environment/information asymmetry:

Fraudsters utilize obfuscation to their advantage. An easy way to do this is operate in an opaque environment, where information asymmetry looms large.

Junior miners fulfill this, as how many people know about mineral reserves? Or how many people have sufficient scientific knowledge to evaluate a promising biotechnology? The average person isn’t a geologist or medical scientist.

Often buzzy, hard to understand words are used in lieu of plain English. Be suspicious of those that can’t explain something concisely without resorting to buzzwords. Yes, something can be complicated, but one should still be able to explain the basic core concepts/benefits to the average person.

Collins Dictionary’s defines a NFT (non-fungible token) as “a unique digital certificate, registered on the blockchain, that is used to record ownership of an asset such as an artwork or a collectible”. Piques your interest, right?

But what if I said a NFT represent a digital asset, but doesn’t mean you own what you bought? If you buy a NFT of the Mona Lisa, you don’t own the Mona Lisa. You own a digital token that represents the Mona Lisa. This unique set of 1’s and 0’s on the blockchain is what you own. It’s worth is only what another person will pay for it.

4) Like attracts like:

Above board people associate with other honest people. Hucksters hang out with sketchy people. Follow known bad actors and bad acting firms, as they tend to pop up again and again. Good companies don’t hire people or advisors previously tied to fraudulent firms.

Intelligence agencies employ this tactic to identify the associates of terrorists. It’s called Social Network Analysis (SNA). Once a suspect is identified, he is used to ferret out other members involved. The government monitors who is called/emailed, who visits them, and money flows.

The chief regulatory officer4 for FTX was an executive as Excapsa Software, an online gaming software company that owned Ultimate Bet. The poker site allowed people to cheat by knowing what cards had been dealt to others. Executives knew and abetted this cheating.

It gets better – the former compliance director of Ultimate Bet is now the General Counsel for Bitfinex. Tether owns Bitfinex.

Trust factor – short circuits due diligence:

People put their trust in those who should know better. In theory it’s an efficient shortcut to rely on those more experienced for investing proof. In practice, not doing your own due diligence will eventually come back to bite you.

Frauds contain a trusted intermediary (or even multiple experts) that attest to the quality of the investment. Importantly, intermediaries do not necessarily have knowledge that something is fraudulent. Often, the expert is economically conflicted. The customer is not represented.

Further, the trusted intermediary is frequently incentivized to sell. Short-term gains are the myopic focus. Fairfield Sentry was the largest feeder fund into Madoff’s Ponzi scheme.

If a fund as well-known and admired as Sequoia vets an investment, surely it can’t be a fraud! Yet Sequoia invested in FTX. Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me…fool me three times, you’re Arthur Andersen.

Arthur Andersen, a former Big Five accounting firm, was involved in three fraudulent cases before being effectively put out of business after surrendering its license to practice public accountancy.

The firm had signed off on the financial statements of Waste Management that had inflated income by over $1 billion between 1992 and 1996. Sunbeam used accounting tricks to create false sales and profits and also used Arthur Andersen as its accountant. The final nail in the firm’s coffin was Enron.

Firms are comprised of people, which are subject to biases like everyone else. However, this isn’t an excuse but rather a reason – they should know better. Voltaire summed it up well when he said, “Common sense is not so common”.

Social proof

Humans take comfort in other people’s assessment of a situation, particularly if it’s someone we know or know of. This is social proof – relying on someone else’s actions to dictate our own because we aren’t quite sure what to do. It’s believing that others’ understanding is more accurate than our own and can be trusted. It’s why celebrities are used in product advertising.

Mimetic desire also comes into play. Human desire is social in nature. Mimetic desire states we don’t want what we want because we want it. Rather, we want what others want because they want it. For a primer on mimesis, see below:

Often frauds are endorsed by big names. These big names themselves are duped by the fraudster, but they’re paid to show up and speak at events or be on the boards of frauds. A big tell is they have no expertise in the area they’re stumping.

Think Tom Brady, Matt Damon, Bill Clinton, Gisele Bundchen, and Tony Blair for crypto. Elizabeth Holmes wins the prize for roping in Former Secretary of States Henry Kissinger and George Schultz, retired four-star general Jim Mattis, former CEO of Wells Fargo Richard Kovacevich, former Secretary of Defense William Perry, and former director of the CDC William Foege.

It makes sense to bring on a well-known figure to laud fraudulent enterprises. It establishes credibility in the eyes of others. People ask fewer questions the prettier the package. At my first job, I was told to make the presentation formatting as clean as possible to invite fewer questions on the underwriting.

It’s human nature to be more aware of what doesn’t fit our expectations of normal. Better to proactively grease the wheels than waiting for squeaky wheels to manifest.

The instigator:

Every movie needs it director – the visionary responsible for the moving parts and ultimate direction. This is the instigator of the fraud. It requires a charismatic individual. Without a certain aura, there is no money to be conned.

Yet at the same time, the mastermind doesn’t look the part of a fraudster. A pretty- young white woman wouldn’t take me in (Elizabeth Holmes). This frizzy haired kid couldn’t punch himself out of a wet paper bag much less steal my money (Sam Bankman-Fried).

There is no universal mold for how fraudsters or criminals look. Our need to compartmentalize into black and white and rely on rules of thumb can lead us astray.

What is universal in a fraud is post hoc rationalization.5 Depending on your level of cynicism, regret ranges from voiced to feigned. If regrets aren’t proffered, that’s because it was someone else’s fault. The instigator claims to have had no knowledge or was coerced.

The fraudsters are geniuses in the lead up, yet immediately regress into a dumbed down version of themselves once the fraud is revealed. “Yes, I was the leader of the organization and intimately involved in the business, but I had no idea fraudulent transactions were taking place.”

It’s not uncommon for the fraudster to live well beyond their means. If it were their money, they might spend it differently. Since it is other people’s hard-earned cash, spending is free-wheeling and sloppy.

They often love the press and the attention that comes with media coverage. Look no further than Sam Bankman-Fried repeatedly talking to the press against the advice of legal counsel and plain common sense.6

Consider FTX buying properties in employee’s names using company funds. Or the spending spree Jho Low went on, which included a yacht, paintings by van Gogh and Monet, a see-through grand piano, and a film company. Mr. Low siphoned billions of dollars from Malaysia’s state-owned 1MDB (1Malaysia Development Berhad).

Typically, the instigator of the con receives the most attention when the scheme unravels. Again, the human element is the most interesting aspect. However, the character cannot be viewed in isolation, as they are part of the recipe to make a cake. The other elements are just as important to the baking process.

Summing up the elements:

Fraud is a system where the elements gain strength from their interconnections. Key components in a fraud are: 1) the mark; 2) the setup; 3) the trust factor; and 4) the instigator. The mark is the duped who, on some level, wants to believe in the scheme no matter how farfetched.

The setup is how the con is facilitated. Red flags are ignored because it’s easy money. It often occurs in opaque environments which come with information asymmetry. Research the people, as bad actors on the periphery of frauds tend to pop up again and again.

The trust factor short circuits due diligence. Efficiency does not equate to effectiveness - those who should know better get fooled as well. Social proof is a powerful concept - it establishes credibility in the eyes of others. It’s why it’s common to find big names endorsing a fraudulent enterprise. They are similarly being conned, though they manage to make some money in the process.

Lastly, the instigator is the driving force. He/she contains a certain charisma, and certainly does look the part of a fraudster (whatever that part actually is). It’s not uncommon for the con to live well beyond their means.

In hindsight, it’s unfathomable that certain frauds occurred. However, we forget that the nature of humanity doesn’t change. We want to believe, and will hang on for the ride so long as times are good. We are driven more by FOMO (fear of missing out) than by prudence.

It’s critical you do your own due diligence. If something sounds too good to be true, it almost always is. Caution is warranted if you can’t understand something and other smart people are scratching their heads. Buzzwords and a general inability to speak plain English should raise concerns and demand a deeper dive. An easy question to ask is if something passes the smell test.

Investing is complex. Fraudsters use this complexity to their advantage, complicating simple things and inducing a sense of FOMO. Having a checklist and consistently using it helps relegate emotions to the background.

The closer a situation fits these factors, the higher the probability there’s something fishy. Use the elements we discussed as a starting point. Feel free to add other items or expound on this post in the comments.

Though the characters and times will change, incidences of fraud will never be fully erased. It’s up to you to educate yourself and question the perceived wisdom of the masses. Trust, but verify.

“Test everything; hold fast to what is good.” 1 Thessalonians 5:21

Because his enemies magically could trace credit cards but not bank transfers? This fails the smell test.

Ultimately 40,000 people invested

Provenance is a fancy word that refers to the art’s record of ownership. It’s used to confirm whether a painting is genuinely from a certain period and by a certain artist. It establishes authenticity. Great works of art have provenance. Period.

Before he was the regulatory officer, he was FTX’s General Counsel

Criminologists call this “neutralization”. It’s used to distance the perpetrator from feelings of guilt.

On top of all the media attention he has received over the last few years.

This is truly excellent stuff. Recommending to everyone I know (all two of them).

Excellent as always. A very easy read and well spaced with illustrations. You’ve really grown as a writer with your pace and formatting.