Why Reflexivity Matters

Connecting "the universe of thoughts with the universe of events"

“This can’t be right,” he thought to himself. Straining his eyes to will the screen to show the quote to be an error, after a few moments he dejectedly slumped into his chair. It was no use. Most of his savings had evaporated over the course of a few days. This wasn’t a matter of losing half of his investment: TerraUSD was down to 3 cents from $1 previously - a 97% loss.

TerraUSD is a class of cryptocurrency called stablecoins that, in theory, are expected to be pegged at a fixed value to fiat currencies (typically the U.S. dollar). Keeping the peg is accomplished 1) by holding an equal amount of highly-liquid, risk-free assets (i.e. cash and short-term government securities1) to the currency’s outstanding value or 2) via algorithms. TerraUSD was backed using an algorithm which means it is a pseudo-peg with sort of dollars. Instead of being backed 1:1 by assets, it relied on financial engineering to maintain the dollar link.

The volatility buffer to maintain the exchange rate was its sister stablecoin, Luna. The mechanism to maintain stability relied on traders arbitraging the values of Terra and Luna. For example, if TerraUSD fell below the $1 peg, Luna would be used to purchase TerraUSD, reducing the supply of TerraUSD and supporting its price.

Unfortunately, many have learned the valuable lesson of how quickly overextended trends can unravel. Simply because many thought that TerraUSD was a stable investment does not make it so. If a company does not have sufficient real reserves to back the peg, once confidence falters, it will collapse.2 The crash shows the demarcation between confidence (e.g subjective reality) and reality (e.g. objective reality).

Investors piled into TerraUSD because of the high, nearly 20% yield on U.S. dollar deposits that were promised on Anchor. This platform takes in money from investors and pays them huge yields for the right to lend out their cryptocurrency. With nearly all of its reserves residing on Anchor, once large TerraUSD withdrawals occurred, it fell below $1. Cascading withdrawals from other investors soon followed as confidence evaporated.

This is an example of reflexivity: imperfect knowledge + acting on this knowledge materially influences prices + more people get drawn in until it reaches unsustainability = eventual wailing and gnashing of teeth as people are caught unawares by the share reversal where inflated expectations tumble to meet reality.

Reflexivity is an important theory to understand as it enters into our everyday life. While financial markets provide excellent examples, they are not the sole source. Buying a house, fads, or politics can be reflexive activities.

We are in the midst of negative feedback loops in the markets, which have been labelled as “wringing out the market’s excesses”. According to current commentary, nearly everybody knew the reversal would happen. But despite the questions, as long as the music played, people danced.

In reality, this insight for the vast majority occurred only in hindsight and they were not able to capitalize on the shift. It’s only when the music stopped playing; but by then, it was too late.

“It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.”

Reflexivity comes in handy to explain what we are seeing today. It is not only applicable to financial markets. Where there are sufficient numbers of “thinking participants” acting on imperfect information, there is reflexivity.

“The idea is that there is a two-way feedback loop connecting thinking and reality. The main feedback is between the participants’ views and the actual course of events.”

The man behind reflexivity:

Before George Soros was a billionaire financier and philanthropist he was born in 1930 in Hungary to a non-observant Jewish family. He was 13 years old when the Nazi Germany occupation began.

His background and father were crucial to subsequent theories. His dad, Tivadar Soros, had survived World War I, which included years in a Siberian prison camp. George’s father knew that to become passive in this situation would almost certainly lead to death. The family purchased documents saying they were Christian during the occupation to avoid being shipped away. Even prior to the occupation, Tivadar was prescient, changing the German-Jewish family name from Schwartz to Soros as Hungary became increasingly anti-Semitic.

In 1970, Soros founded Soros Fund Management (later renamed Quantum Fund), a hedge fund that bet on macroeconomic trends. His most famous trade, “breaking the Bank of England”, consisted of betting against the British Pound, earning him $1 billion in profit in one day.

The setup: the UK had joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism or ERM in 1990, which was the precursor to the EU. Countries agreed to fix their exchange rates with each other instead of letting them float (e.g. capital markets determine the rates). The exchange rate was fixed to Germany’s Deutschmarks within a band of +/- 6% of the agreed upon rate. The issue with fixed exchange rates is they require maintenance to hold steady as the market can apply pressure if it disagrees with what the exchange rate is fixed at.

To hold the currency stable to the peg requires vast reserves of foreign currency. The other way to manipulate currency rates is via interest rates. Higher interest rates, ceteris paribus, cause currency appreciation. Side note: this is a big reason why the U.S. dollar has been so strong - the Fed is raising interest rates. More people exchange other currencies for dollars in order to benefit from rising risk-free interest rates.

By 1992, the British pound was overvalued compared to the Deutschemark band peg. Also, the UK had higher interest rates than it would have liked with the economy being in a recession. Interest rates had to be held at higher rates to support the fixed exchange rate, particularly as sterling had sunk to the bottom end of the +/-6% band.

However, crucially, the market still believed in the UK government’s guarantee that the fixed rate would hold. Soros correctly recognized that people’s beliefs did not match reality and began building up a short position for months. Once the massive sell-off in pounds began, the Bank of England was unable to support the band.

And there was no support from the German Bundesbank on the horizon, with traders seizing on the report that the President of the Bundesbank would allow “one or two currencies” to come under pressure instead of altering its own currency. As the fire gained oxygen, the Bank of England didn’t have enough currency left to support the exchange rate. Traders smelled blood in the water and went full throttle, capitalizing on the Bank’s weakness. The end of the UK’s involvement in the ERM was nigh, and it withdrew from the ERM.

Reflexivity in a nutshell:

Principle #1: No one knows everything. We are all fallible.

Principle #2: People’s imperfect thinking/knowledge base leads to actions that influence overall events.

Economics sets itself up to fail with its universal laws because there is no universal constant. It is not math or physics. Yet economists treat it as if it were so. We do not have complete information across the complex adaptive systems known as the global economy.

All systems have lags. Consider recent retailer earnings:

“Major U.S. retailers that recently scrambled to restock shelves amid product shortages disclosed this week that their stores are now packed with too much merchandise, and some are even doing what was unthinkable just a few months ago: discounting unsold goods.”

After struggling to procure sufficient inventory given worldwide supply chain issues, companies over-ordered compared to current demand and are stuck with too much inventory. It’s not as if this were a one-off: Walmart, Target, Abercrombie & Fitch, Macy’s, Costco, and Gap (to name a few) all discussed inventory imbalances. Yet the market did not bake this in, leading to sharp declines after earnings.

Reflexivity and fallibility are part of the human condition:

Fallibility is inherent in the complex world we live in. Consciously, humans can only process 50 bits of information per second. This is minuscule compared to the 11 million bits of information our senses are taking in from the environment. And this too, is tiny compared to the over 300 exabytes of human-made information3. In the face of this complexity, we simplify information into generalizations, mental models, dichotomies, etc. Further complicating matters is that these mental constructs are based on our subjective experiences. There is no Cartesian mind-body separation; you aren’t even a mainly rational, disembodied intellect.

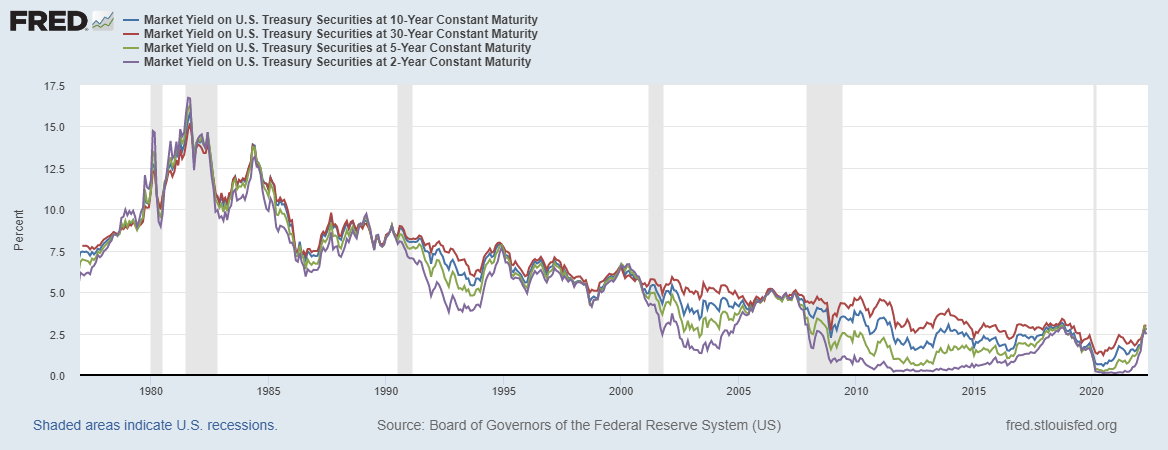

Like it or not, how, when, and what context you grew up in colors your viewpoint. Add to this your decisions in life and what time period you lived in. Many were caught unawares when Central Banks undertook quantitative easing (QE) in response to the Great Financial Crisis. Further, no one previously had lived through the structural decline in interest rates witnessed over the past 30 years.

Reflexivity occurs in situations where the participants are sentient. Humans want to understand the world and make an impact. This impact is not necessarily charitable but rather applies to advancing one’s own interests. There must be a significant number of participants to affect the system. Enough people have to both believe and act on these beliefs to influence things.

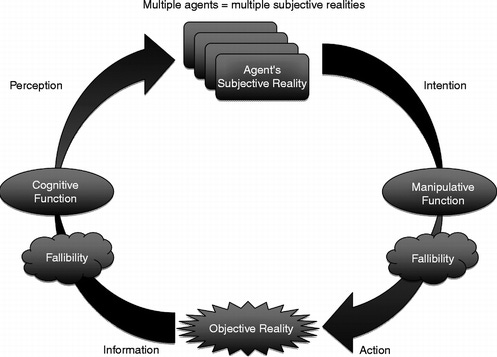

Soros categorizes thinking into two functions: cognitive and manipulative. Reflexive systems are dynamic and based on the interplay of the cognitive and manipulative functions.

Cognitive is the passive observer role. Manipulative is the intentionality of it; the playing an active role in affairs. Neither is purely independent from the other. Both are subject to fallibility and introduce uncertainty into the system.

“Reflexive feedback loops between the cognitive and manipulative functions connect the realms of beliefs and events. The participants’ views influence but do not determine the course of events, and the course of events influences but does not determine the participants’ views. The influence is continuous and circular; that is what turns it into a feedback loop.”

Reality is divided into subjective and objective. Subjective speaks to an individual’s thoughts and mental filters (how they interpret things). Objective covers all observable facts. Saying, “It’s raining,” is an objective statement. Whether people believe there’s rain or not cannot change what is. As such, only one objective reality exists, but there are many subjective views. To Soros, “reality is halfway between free will and determinism”.

Reflexivity can come in the form of reflexive relations, like relationships or politics, which link together the subjective aspects of reality. Reflexive events, on the other hand, like the euro crisis or COVID-19, connect subjective and objective aspects. Lastly, an individual reflecting on his own identity is self-reflexivity, as it is occurring within a single subjective reality aspect. Without subjectivity there is no reflexivity.

Soros believes that reflexivity challenges the idea that natural and social science can be unified. The difference between the two comes down to human uncertainty. We do not know all probabilities of future states, or even if we have captured all possible future states. This is Knightian uncertainty4, which differs from risk. “Risk is when there are multiple possible future states and the probabilities of those different future states occurring are known.”

“Social science’s difference comes down to thinking as a causal role. This is not the case for natural phenomena – events happen irrespective of the subjective beliefs of the observers. Only the cognitive function is engaged in natural science observations. It is true that “based on this knowledge, nature can be successfully manipulated. That manipulation may change the state of the physical world, but it does not change the laws that govern the world. We can use our understanding of the physical world to create airplanes, but the invention of the airplane did not change the laws of aerodynamics.”

Social events see reflexive feedback loops intertwined within the aspects of objective and subjective reality. At times the subjective and objective come closer together, and sometimes they expand away from each other. “The two aspects [subjective and objective] are aligned, but only loosely – the human uncertainty principle implies that a perfect alignment is the exception rather than the rule.”

Soros said that the achievements of natural science were too alluring for economists and other social scientists not to try to produce similar “generalizations of universal and timeless validity”. He calls this “physics envy”. These natural science treatments “do not ensure that human behavior is always governed by reason”.

“In order to achieve the impossible, they invented or postulated some kind of fixed relationship between the participants’ thinking and the actual course of events…the mainstream economic theory currently taught in universities…is an axiomatic system based on deductive logic, not on empirical evidence. If the axioms are true, so are the mathematical deductions. In this regard economic theory resembles Euclidian geometry. But Euclid’s postulates are modeled on conditions prevailing in the real world while at least some of the postulates of economics, notably rational choice and rational expectations, are dictated by the desire to imitate Newtonian physics rather than real-world evidence.”

He attributes some of these economic errors to the theory of perfect competition, which assumes perfect knowledge. Later this was modulated to universally available perfect information. This approach “reached its apex with the rational expectations and efficient market hypothesis in the 1960s and 1970s…The efficient market hypothesis5 allows economic theory to lay claim to the status of a hard science like physics. And market fundamentalism allows the financially successful to claim that they are serving the public interest by pursing their self-interest.”

In fact, if economic theory did produce universally valid laws such as a purely efficient stock market, Soros says economic profit would not be possible:

“if all changes were to take place in accordance with invariable and universally known laws, [so that] they could be foreseen for an indefinite period in advance of their occurrence, … profit or loss would not arise.”

In summary, human uncertainty prevents the social sciences6 from producing results comparable to physics along with, in other ways, the scientific method. (Could this be a large, hitherto unexcavated reason behind the replication crisis? I hope to explore this in a subsequent post.)

“Any valid methodology of social science must explicitly recognize both fallibility and reflexivity and the Knightian uncertainty they create. Empirical testing ought to remain a decisive criterion for judging whether a theory qualifies as scientific, but in light of the human uncertainty principle in social systems it cannot always be as rigorous as Popper’s scheme requires. Nor can universally and timelessly valid theories be expected to yield determinate predictions because future events are contingent on future decisions, which are based on imperfect knowledge. Time- and context-bound generalizations may yield more specific explanations and predictions than timeless and universal generalizations.”

In fairness, scientists are human and thus bring with them their own biases and pre-conceived notions:

“they influence the selection of facts but they do not influence the facts themselves. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle showed that the act of observation impacts a quantum system. But the discovery of the uncertainty principle itself did not alter the behavior of quantum particles one iota. The principle applied before Heisenberg discovered it and will continue to apply long after human observers are gone. But social theories – whether Marxism, market fundamentalism, or the theory of reflexivity – can affect the subject matter to which they refer.”

Reflexivity as viewed through financial markets:

Financial markets represent a solid testable proposition with respect to Soros’s hypothesis of reflexivity rather than efficient markets.

Fallibility: Financial asset prices do not represent fundamental values because that is not their aim; they reflect participants’ expectations of future market prices. The fallibility of market participants means their expectations about discounted cash flows are most likely divergent from the objective reality. The delta could range from negligible to material.

Reflexivity: Financial markets are not solely passive, as they can affect the discounted cash flows they are supposed to reflect. Behavioral economics focuses on half of the reflexive process: the cognitive fallibility behind asset mispricing. The second order of how action and behavior from these beliefs impacts the mispricing of fundamentals is not sufficiently considered.

As a result, participants’ divergent expectations from reality are the generic cause of price distortions. Soros believes the norm in economics is “near-equilibrium”:

“Whereas economics views equilibrium as the normal, indeed necessary state of affairs, I view such periods of stability as exceptional…Near-equilibrium yields humdrum, everyday events that are repetitive and lend themselves to statistical generalizations. In contrast, far-from-equilibrium conditions give rise to unique, historic events in which outcomes are uncertain but have the capacity to disrupt the statistical generalizations based on everyday events. Rules that can usefully guide decisions in near-equilibrium conditions can be misleading in far-from-equilibrium situations.”

The collapse of the Terra token and SPAC boom-bust are examples of fallibility bleeding into expectations until participants’ subjective realities can no longer sustain the delta from the objective reality.

As financial markets are systems, they carry with them positive and negative feedback loops. Positive feedback loops are self-reinforcing and can drive prices away from fundamentals. Negative feedback loops are self-correcting in that they tamp down the positive feedbacks.

“Negative feedback loops tend to be more ubiquitous but positive feedback loops are more interesting because they can cause big moves both in market prices and in the underlying fundamentals. A positive feedback process that runs its full course is initially self-reinforcing in one direction, but eventually it is liable to reach a climax or reversal point, after which it becomes self-reinforcing in the opposite direction. But positive feedback processes do not necessarily run their full course; they may be aborted at any time by negative feedback.”

Positive feedback loops can become so massive that they overtake everything else in the market. Look no further than SAAS (software as a service) stocks for a great example:

SAAS stocks went b-a-n-a-n-a-s for years (e.g. FAANG). Before they took off, EV/Sales in the mid to high-single digits were considered expensive. During the height of their popularity, it was not uncommon for stocks to trade above 30x EV/Sales.

Sell-side analysts would contort themselves into pretzels to underwrite their buy recommendations, using multiples many years in the future to justify the current price. People raved about the new structural change in these stocks’ multiples driven by their recurring revenue business model. Funds who piled into these stocks in concentrated positions reaped huge gains. If you doubted, you were run over in trying to short these stocks and dismissed as part of the old economy. This is a self-reinforcing positive feedback loop.

SAAS stocks being expensive was not a catalyst in and of itself. Something(s) had to change in prevailing market conditions to arrest their favorability. Inflation sustainably coming back into our purview and the Fed’s belated move to raise interest rates quickly introduced a negative feedback loop into the system. So too did the evidence of slowing economic growth. These led to market participants’ expectations changing, which then went on to impact SAAS stock prices. This same line of thinking could be applied to the unprofitable, “to the moon” stocks. Now the focus is on profitability rather than growth at any cost.

Boom-bust processes and reflexivity:

The constituents of a bubble are: 1) an underlying trend that prevails in reality and 2) a misconception pertaining to this trend. In other words, the trend and misconception positively reinforce each other. Negative feedback loops test the process along the way. If it overpowers these tests, expectations are increasingly removed from the objective reality. At some point, the trend violently reverses and becomes self-reinforcing in the opposite direction. Prior to the violent reversal, doubts grow and the trend is increasingly questioned, but inertia for the time being wins out.

“Boom–bust processes tend to be asymmetrical: booms are slow to develop and take a long time to become unsustainable, busts tend to be more abrupt, due to forced liquidation of unsustainable positions and the asymmetries introduced by leverage.”

A typical boom-bust cycle starts out with (A) and (B), where a new positive earning trend is not widely known. Acceleration occurs during (B) and (C) as recognition and reinforcement propels the trend. However, a testing period can come where either earnings or expectations falter (C) and (D). It is not enough to arrest the trend, which develops greater conviction and is not derailed by setbacks (D) and (E).

The divergence between subjective realities and the objective reality widens (E) and (F). The “moment of truth” occurs when reality can no longer support overextended expectations (F). Though participants do not believe in the trend to the same extent, they continue to “play the game” in this “twilight period” (F) and (G). Once the crossover point (G) is attained, the trend loses all support and undergoes a sharp downward acceleration (G) and (H), spreading misery across participants and constitutes the crash. The trend overshoots to the downside, some stabilization takes place, and to an extent prices recover (H) and (I).

“The simplest case is a real estate boom. The trend that precipitates it is easy credit; the misconception is that the value of the collateral is independent of the availability of credit. As a matter of fact, the relationship is reflexive. When credit becomes cheaper and more easily available, activity picks up and real estate values rise. There are fewer defaults, credit performance improves, and lending standards are relaxed. So, at the height of the boom, the amount of credit involved is at its maximum and a reversal precipitates forced liquidation, depressing real estate values. Amazingly, the misconception continues to recur in various guises.”

The principles of reflexivity explain the behavior of financial markets along with social sciences drawbacks (i.e. human uncertainty principle/Knightian uncertainty). What we are witnessing today in the financial markets is likely somewhere in the twilight period to perhaps approaching an overshoot phase (between points F and H).7 Unlike the boom-bust chart, market moves are jagged, so it’s difficult to know a priori precisely where we are in the cycle. It’s only in hindsight where more perfect knowledge is gained.

Great discoveries show us everyday data in a new light. Indeed, often once they are put together, we are surprised we didn’t see the pattern before. So it is with reflexivity: Soros took something we are well-acquainted with - the imperfectness of human knowledge (“nobody knows everything”) and our actions based on this information - to explain why financial markets can act as they do.

To be sure, getting the timing correct remains more of an art than a science - “Markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”. Yet reflexivity gives us a good, explanatory framework: if collectively enough people agree and act on certain expectations (“subjective reality”), a material divergence from what actually is (“objective reality”) occurs. At some point, the expectation trend based on subjective reality becomes unsustainable and a savage reversion occurs.

Author’s Note: This post is based on George Soros’s Journal of Economic Methodology article, “Fallibility, Reflexivity, and the Human Uncertainty Principle”. Thanks to Neckar Value for providing the inspiration via his excellent piece on George Soros’s life.

The safest stablecoins would be backed by cash and short-term government securities. Tether, the most popular stablecoin, uses riskier instruments like commercial paper and secured loans to companies/other cryptocurrencies to maintain the peg. So far it has retained its peg, but concerns remain. The big question swirling around Tether is what assets are backing the peg. How much of the reserves are cash/short-term government debt compared to riskier, relatively more illiquid investments? What is the firm’s true reserve level? Thus far, the company has refused a reserve audit (big red flag).

LOUDER FOR THE PEOPLE IN THE BACK: IF YOU INVEST IN SOMETHING THAT IS SUPPOSED TO HAVE REAL, HIGHLY-LIQUID INVESTMENTS BACKING IT AND IT DOES NOT HAVE THESE ASSETS IT WILL AT SOME POINT COLLAPSE.

One exabyte is equal to 1 million terabytes.

Knightian uncertainty de facto cannot be quantified, though it remains possible to identify trends and changes in trends without exact quantification.

Efficient market hypothesis states that share prices reflect available information. Thus, it is impossible to beat the market over a long time period since pricing changes only occur with new information.

Economics is considered a social science because it deals with human behavior in its social and cultural aspects. Other social sciences include anthropology, sociology, psychology, and political science.

I tend to think we are somewhere in the twilight period to reversal phase.