“Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth.” - Fyodor Dostoevsky

Pain was a constant companion for Joseph Townend. He was born on October 14th, 1806, as the eleventh of ultimately twelve children (though four died in infancy). At the tender age of three, his apron caught on fire as he was lifting a kettle off its hook.

“I distinctly remember being laid upon the floor, and having my wounds saturated with treacle, in order to extract the fire. My right side close up to the pit of the arm, and my arm down to the elbow, were severely burnt, so much so, that all feeling for a time was gone…What torture I endured, the twelve months I was confined to my bed!...after many painful and unsuccessful attempts to keep the arm from adhering to my side, the struggle was given up, and the arm, down to the elbow, was allowed to grow to my side.”

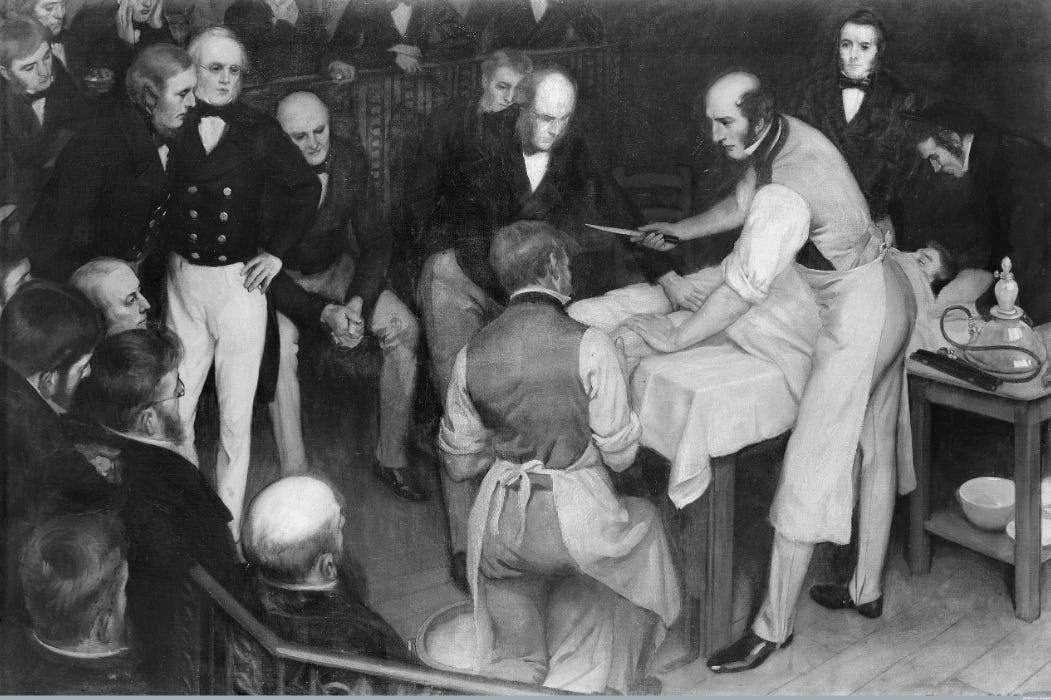

And pain did remain his faithful companion as he went to work at age seven in the cotton mills. This being the early 1800’s, he was working thirteen to fourteen hours a day to support his impoverished family. At age eighteen, he “wrenched” his wrist. Over a month later, a “most exquisite” pain nearly overwhelmed him as a doctor cut his arm from the side without the benefit of any anesthesia, which was decades from being invented.

His pain was not merely physical, it also was present due to his low social standing. Several days after his surgery, the surgeon became incensed when Townend offered his left hand as a handshake (as his right arm was the one operated on). The surgeon exclaimed, “Do you offer a gentleman your left hand?

“Then, seizing my right hand he dragged me off the bed into the middle of the room. I leaned to my left side, and holding up my right foot, I tried to keep up my poor arm. With violence he struck at the same moment with one fist the knee, and with the other the elbow, sternly exclaiming – ‘Stand up man; you have not your mother for your doctor now!’ Immediately my leg and foot were covered with blood’ and on the web being unloosed, I saw it was turned black: and my poor side was drenched in blood, and smoked almost like a kiln.”

The fact that he experienced excruciating pain is obvious. Yet he was able to influence the sensations and give an ultimate meaning to his suffering beyond himself due to his upbringing and perspective. This occurs independent of whether we deem his worldview to be accurate or foolhardy. In other words, to some extent, your perspective is your reality.

“Townend’s encounter with ‘exquisite’ pain was rich with signification. The different meanings he gave to his suffering had profound effects on the ways he experienced the agonizing sensations of undergoing major surgery without anaesthetics. These meanings did not emerge ‘naturally’ from physiology: his corporal sensations were profoundly affected by his interpretation of what was happening to him…

Townend’s relationship to his pain was a learned exegesis. His suffering was inextricably entangled with his upbringing as a Methodist. His narrative of the redemptive character of bodily suffering could not be separated from his spiritual beliefs. Those beliefs had been deeply ingrained in him from infancy, and they had been reinforced numerous times as he witnessed the agonized illnesses, injuries, and deaths of family members, friends, and neighbours.” - Joanna Bourke

What is pain?

“Things which all men know infallibly by their own perceptive experience, cannot be made plainer by words. Therefore, let Pain be spoken of simply as Pain.” – Dr. Peter Mere Latham

Like a picture, the meaning of pain could take up thousands of words. It is part and parcel of life. The evolution of species and of oneself comes with pain and suffering. It can apply to a toothache, to headaches, phantom limbs, the death of a loved one, and break-ups. Yet it is hard to pin down into absolutes as it is not merely the result of stimuli acting upon nerve endings.

The IASP (International Association for the Study of Pain) defines pain as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” It “is always a personal experience that is influenced to varying degrees by biological, psychological, and social factors.” It “cannot be inferred solely from activity in sensory neurons.”

Pain has often been described as an “it” – an entity outside ourselves. In reality, it is an event that is experienced and participates in and influences how we view ourselves and the world. It is a shared language. It is a matter of feeling in that it explains the way we experience something. We revert to animalistic metaphors to describe our pain because of its base nature. It is part of the human experience throughout the eons.

“Pain is not the thing or object that one is feeling, it is what it is like to feel the thing or object.” – Guy Douglas

Speaking of pain as a type of event delineates between a pain-situation versus pain-experience. Contrast needs to be drawn because it is possible to experience zero pain in a pain-situation or to be in pain without being in a pain-situation. For those fond of BDSM, which stands for Bondage, Discipline, Dominance, Submission, and Sadomasochism) is a ready example of being in a pain-situation yet not experiencing pain as such.

Describing pain under the “type of event” model also disentangles the false Cartesian dichotomies between pain in the body and in the mind. The same brain centers that process bodily pain are activated with emotional pain. Thus, it is no surprise that taking pain medication like Tylenol (e.g. acetaminophen) or ibuprofen reduces the perception of emotional pain. These drugs work by reducing inflammation throughout the whole body.

It’s important to distinguish between pain and nociception, which are often used interchangeably. Nociception refers to the physiological process where nerve endings (called nociceptors) are activated and transmit the perception of pain through the nervous system. Literally, nociception concerns impending or actual tissue damage. It is the reflex that forces your hand to pull back upon touching a hot stove (before you’re even aware of what’s happening). The nociceptors send signals to the brain, where subjective feelings of pain and distress are produced by the brain.

The relationship between peripheral nerve activation and distress is not one-to-one. In other words, nociception does not automatically equal pain, nor does pain necessarily mean nociception. An amputee with phantom limb pain experiences discomfort without nociception. Someone can get into freezing water without any sensation of pain, while another can’t stand it.

Distilling pain down into nociception alone is reductionistic as it’s separated from the subjective felt experience of pain. The firing of neurons occurs both in nociception and the brain’s experiencing pain.

Consciousness is required for the subjective, felt experience of pain. On the other hand, nociception exists without consciousness.

“Nociception is an ancient sense. It is so widespread and consistent across the animal kingdom that the same chemicals, opioids, can quell the nociceptors of humans, chickens, trout, sea slugs, and fruit flies - creatures separated by around 800 million years of evolution. But since pain is subjective, it is difficult to tell which creatures have it.” - Ed Yong; An Immense World

Our shortcomings in determining the consciousness of non-human creatures result in difficulties ascertaining to what extent animals feel pain. Consensus is mammals can feel pain as we do. The jury is out for fish, insects, and crustaceans.

Pain researchers in the 1950s found that most people perceived pain around similar intensities, but their threshold to react to it varied enormously. The “ability to perceive pain depends upon the intactness of relatively simple and primitive nerve connections,’ while reacting to pain was ‘modified by the highest cognitive functions and depends in part upon what the sensation means to the individual in the light of his past experiences.”

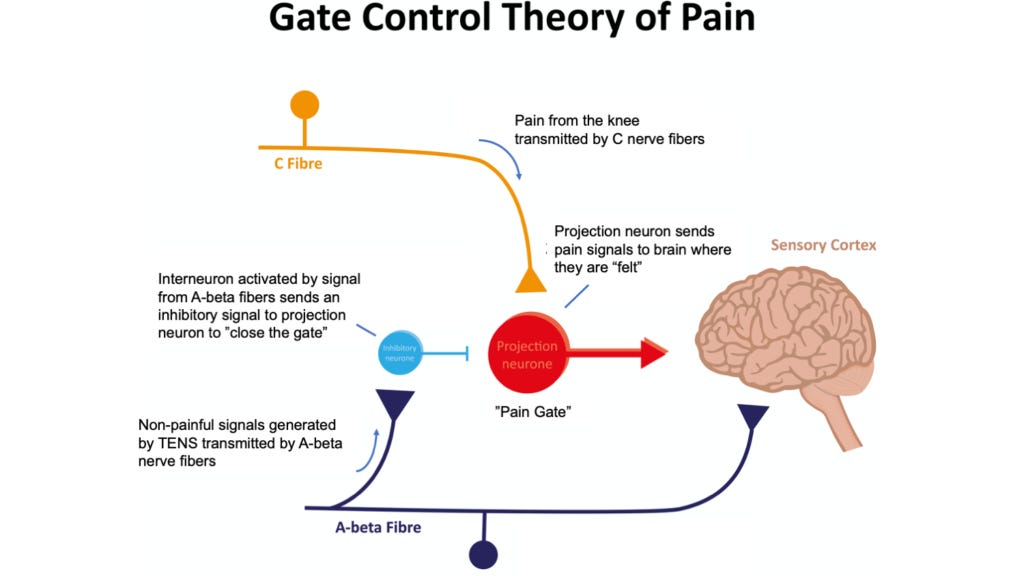

Further work led to the gate control theory over the next decade. Importantly, this was the first pain theory to incorporate psychological factors as a central role in the pain experience. In essence, gate control theory states there is a mechanism in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (the “gate”), which controls the perception of pain.

An open gate means pain signals are passed to the brain, and vice versa for a closed gate. The belief is this helps explain why the common response after slamming your finger in the door is to rub it or suck on it. Pain signals are then inhibited going up to the brain as the theory is non-painful input closes the gates to painful input. If true, it helps explain why TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) devices and massage work well for pain management.

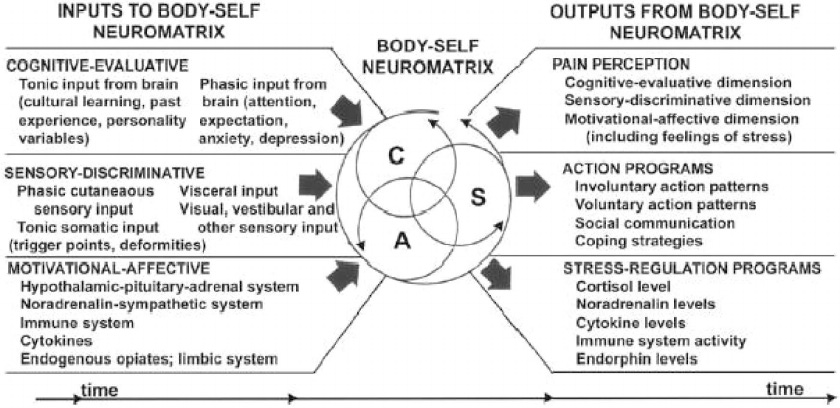

Currently, a predominant model of pain is psychologist Ronald Melzack’s neuromatrix of pain, wherein the perception of pain comes from a complex array of neural inputs that’s in relation to one’s genetics and the interplay one’s environment has on the brain and nervous system. This theory was presented to bridge shortcomings gate control theory has in addressing phantom limb pain and chronic pain issues.

“Pain, then, is produced by the output of a widely distributed neural network in the brain rather than directly by sensory input evoked by injury, inflammation, or other pathology. The neuromatrix, which is genetically determined and modified by sensory experience, is the primary mechanism that generates the neural pattern that produces pain. Its output pattern is determined by multiple influences, of which the somatic sensory input is only a part, that converge on the neuromatrix.” - Dr. Ronald Melzack

The reality is pain is much more complex than nerve endings being stimulated by a noxious stimulus: it is context-dependent and narrative-driven. Emotions and cognitive states share a relationship to pain in that they can lead to increased or decreased pain.

However, it is much simpler to talk about the physiology of pain than the meaning. Pain is multilayered and the physiological portion is the bottom layer. The ways in which we ascribe meaning to, cope with, and experience pain are multifaceted. Our perception of pain is influenced by culture, our worldview, our environment, our mind, and our genetics.

Red-haired people typically have a high pain threshold. One could argue that those who lived before anesthesia were better able to tolerate pain.1 Or perhaps it came down to having no choice in the matter.

Interestingly, when anesthesia was first introduced it encountered backlash. People didn’t want to meet their Maker in an altered state. Doctors even recommended not giving the supposedly unsaved pain medicine because it may take away the opportunity to turn back to God right before death! It was not until the 1950s for pain relief to be seen as integral to those who had no hope of escaping an agonizing death. In places like Sub-Saharan Africa, control of severe pain was non-existent until 1990.

In present day, the myth that black people perceive less pain persists. Half of a sample of white medical students/residents believed that black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive than white people’s or that their skin is thicker according to a 2016 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science. Unsurprisingly, black patients routinely see their pain undertreated. A meta-analysis covering twenty years of studies found black patients were (22%) less likely than white patients to receive any pain medication.

Ultimately, pain is a warning system. All is not well and demands your attention to remediate. Feelings serve as a similar system, biding us to investigate. Pain prods us towards action. And as with stress, it tells us what values we hold dear.

“We can ignore even pleasure. But pain insists upon being attended to. God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pains: it is his megaphone to rouse a deaf world.” – C.S. Lewis

If you have unexplained pain or illnesses that you have not been able to figure out, I highly recommend diving into somatization. This is where an inability to cope with emotions or psychological factors (whether due to trauma or just plain life) manifests itself in the body in the form of physical symptoms.2 Ever had a stress headache? Or a panic attack? That’s somatization. Somatization symptoms have been positively associated with chronic low back pain. George Soros would back this up:

“I rely a great deal on animal instincts. When I was actively running the fund, I suffered from backache. I used the onset of acute pain as a signal that there was something wrong in my portfolio. The backache didn’t tell me what was wrong – you know, lower back for short positions, left shoulder for currencies – but it did prompt me to look for something amiss when I might not have done so otherwise.” - George Soros

When trauma patients are triggered, they are literally reliving the physical symptoms and re-living the event(s). Importantly, it occurs outside our conscious awareness. We have an idea of what we are experiencing but do not know why. It is extraordinarily helpful to journal or to speak someone to tease out these emotions. Like burping, it’s “better out than in.” Bringing these feelings out into our conscious awareness allows us to look at them from different vantage points and assess their accuracy. I have been told to think of these feelings like holding a ball in your hand to gain distance and the ability to think analytically.3

Of course, the above connotations of pain are referred to in a negative sense. It would be remiss of me to categorize all pain as “bad”. As discussed, pain has a large, perceptual component to it – in that it is shaped based on our meaning of it. The muscle burn I feel while working out is based on the context. The sensation I feel with tears or spasms is far from enjoyable. Humans are meaning making machines. Our interpretations, our narratives about pain can shape both the pain and ourselves. We cope best when we make sense of things into a coherent whole.4

“He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

The via negativa of pain:

The Latin phrase, “via negativa” is utilized by mystics who find more apt descriptors of God to come from what He is not rather than attempting to explain what He is.5 God is a not thing, in that He transcends anything the mind can comprehend…He is essentially unknowable.

Via negativa is a useful way to analyze pain. While we can more easily get into the mind of someone afflicted with pain than we can with God, we still may not be able to fully comprehend their pain. Further, the multi-faceted nature of the pain experience makes it easier to frame absolutes in the form of negatives.

Pain is not a mind-body dichotomy. Pain is pain, whether emotional or physical. The Westernized world holds physical pain in higher esteem than emotional despite both relying on a shared neural circuitry. “Negative experiences based on social pain can activate the brain areas related to the emotional components of physical pain.” The brain doesn’t delineate between physical and emotional pain. They both light up the same brain areas and they both hurt. Further, when we see someone suffering, in a way we too suffer. These are called mirror neurons.

Pain is not purely comparative. It is relative. Some “thing” that is painful for me may not be as painful to you.

Pain is not fair. It is not an equal opportunity provider.

Pain does not define our humanness. It is certainly implicit in human life, and influences our actions, but it is not our main quality. It does not signify anything regarding our intrinsic worth.

For centuries, people believed that one’s suffering was the result of unatoned for sin(s). Childbirth pain was said to be a consequence of Original Sin. Despite Jesus’ teachings, the perceived correlation of sin and suffering continued well into the twentieth century.

“As He passed by, He saw a man blind from birth. And His disciples asked Him, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he would be born blind?” Jesus answered, “It was neither that this man sinned, nor his parents; but it was so that the works of God might be displayed in him.” – John 9:1-3

For those non-white, poor, and/or female, pain was used as confirmation that they were “less than” white, elite males. The people deemed to be subhuman could not win – either their cries reflected their weakness, or their fortitude in the face of suffering showed their nervous system was different from the whites. This assumption led to the perverse nature where more pain was allowed (or relief withheld) because, after all, they do not feel as “we” do. Unfortunately, as previously discussed, these views have not been completely remediated.

“Although ‘the knife of the anatomist … has never been able to detect’ anatomical differences between slaves and their white masters, he admitted, it was obvious that slaves possessed ‘less exquisite’ bodies and minds. Because of their dulled sensitivities, slaves were better ‘able to endure, with few expressions of pain, the accidents of nature’." - Joanna Bourke

Implied sub-humanness was not restricted to races, as it was also class-based as we saw with the opening story of Joseph Townend. The same argument regarding high pain fortitude was made with respect to animals and even infants!

Prior to the 1870s, infants were believed to be highly sensitive to pain. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, scientists and doctors thought “infants were almost totally insensible to pain”. Their reactions to painful stimulus were derided as “simple reflexes”. This warped viewpoint only began changing in the 1980s. While more subtle nowadays, we implicitly fall into the trap believing the person may deserve it or that they are malingerers (pretending).

People with chronic pain were often treated with the suspicion of “trying to pull one over” on the doctor. Their pain did not fit into the neat box doctors sought. Instead, they were routinely stigmatized and viewed as blameworthy.

“If you complain a lot, you’re bound to get on somebody’s nerves. And there are times when the person would say to you, ‘I know you’ve got it, pain, but quit bitchin’ about it.’” - Chronic pain patient in The Story of Pain

The prevalence of chronic pain continues today, with a whopping 20% of Americans suffering in some form. Germany, Hong Kong, Norway, Denmark, and Hong Kong have chronic pain prevalence ranging from 18% to 24%. A meta-analysis found that 18% of the general population in developing countries have chronic pain. Variation between countries ranged from 13% to 51%.

Pain is not a zero-sum game. My pain does not offset yours.

Pain is not the final result. It can be modulated. We can’t change the hand of cards we were dealt, but we are in control of how we play the hand.

It is true that certain pains cut so deep that we are irrevocably changed. In turn, we can use these changes as part of the redemptive process. We can influence pain both in our perspective of it and what we do with it. Redemption is not negation of what happened; it’s taking what literally and undeniably is and turning it into something better.

Humans are unique in our desire for purpose and meaning. We care about our legacy. There are stories a-plenty of how people turned the pulp of pain into something that positively changed other’s lives. Rob Kenney is behind the YouTube channel “Dad, How Do I?”, which teaches lessons typically given by fathers to sons. He started the channel to teach others what he never learned as his own father left the family when he was a child.

The contradictory nature of pain:

Pain is discriminatory and anti-discriminatory. Every person is subject to pain. But the pain is not equally distributed.

“Many underprivileged people have to fight to have their misery noticed, but others might themselves not register an occurrence as distressing simply because it is so typical. Throbbing muscles, aching backs, diarrhoea, and hunger pangs may be interpreted as experiences simply ‘engrain’d in very living’. According to one highly influential sociological approach, pain ‘disrupts biographies’—in other words, suffering cause a person’s life to deviate from its expected course. However, this may only be the case for lucky or affluent members of our communities. For the rest of us, being-in-pain might just be our expected biography.” - Joanna Bourke

Pain can soften and harden.

“I doubt not that some natures are softened by pain, but many are hardened.” – Isaac Burney Yeo

Pain is isolating and connecting. Those in pain experience an aloneness that transcends words. You are in the world, but not a part of it. The intimate knowledge of this separateness adds to your suffering.

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

― James Baldwin

Similarly, pain separates one from himself. People do not reference pain as their homeostatic point but as the anomaly. Pain is the otherness than results in our otherness feeling towards ourselves and the world.

“Joy makes us hurry from the house, pain makes us enter it; joy makes us open the window, pain makes us close it. Joyous, we seek light, movement, noise, men; unhappy, we want darkness, rest silence, solitude.” – Paolo Mantegazza

Suffering in silence has been highly valued in our Western society. We can attribute a fair portion to Judeo-Christian values, which have been translated into meaning you must have done something to deserve this. Especially for men, the sentence for expressing specific pains has been particularly harsh. You’re a baby, or weak. Emotions, and specifically pain emotions, are reserved for women.

It’s important to have a witness in your pain. The witnessing connects us on a deeper level that does not rely on an intimate knowledge of that pain. It is the gumption that we are all in this together: “today you…tomorrow me”. Witnessing is not necessarily solving the pain problem (as after all sometimes it cannot be solved). It is coming alongside someone to say, “You are not alone.”

With the advent of the internet and borders between nations crumbling, never before can we stand witness to pain as now. It threatens to overwhelm if one isn’t careful. Christianity states to love our neighbors as ourselves. Instead of asking who is our neighbor, perhaps the better question to ask is, “Who isn’t our neighbor?”

“Compassion is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It's a relationship between equals. Only when we know our own darkness well can we be present with the darkness of others. Compassion becomes real when we recognize our shared humanity.” - Pema Chodron

Pain is purposeless and purposeful. Though living standards have dramatically improved across the centuries, there remains much pain. Look no further than the nightly news.

By purpose, I don’t necessarily mean there’s a rational reason. Rather, pain can be used in a redemptive way. It comes back to the two-way street between the perception of pain and the pain itself. Pain can transform. It can catalyze growth. As Susan Cain says in her book Bittersweet, “Whatever pain you can’t get rid of, make it your creative offering.”

Pain can be deeply intimate in the moment and hard to recall after. After the pain event, I have only the most tenuous grasp on how it felt. Instead of specifics I talk in generalities - “It felt miserable.” Yet in the midst of the pain experience I can tell you about migraine that manifested as an ice pick in the back of my right eye that kept the same beat as my heart. How no position brought any comfort or how I cowered in the fetal position because any movements would cause sharper stabs.

As bad as pain feels, the relief feels even better. I’ve had migraines for years now. There is little to rival how good one feels after an eight out of ten pain migraine is broken. Though I feel like a normal day that is pain-free, the contrast from the earlier pain yields unbridled gratitude. I wish to hold on to that feeling, but it subsides by the next morning.

Ironically, this is the reverse of loss aversion, which says we prioritize avoiding losses more than an equal gain because we feel more pain with losses than happiness with gains. The famous statement is that psychologically, losses hurt twice as much as gains. Never mind that this concrete principle in economics has had some holes poked through it.6

Pain is disabling and enabling. It disables the individual and enables the community. It is debilitating and a catalyst for change.

Those in the midst of pain acutely feel Emily Dickinson’s words:

Pain — has an Element of Blank —

It cannot recollect

When it begun — or if there were

A time when it was not —It has no Future — but itself —

Its Infinite realms contain

Its Past — enlightened to perceive

New Periods — of Pain.

Even so, never do we see an outpouring of support and communal support than in response to pain. In the Western world, look no further than after 9/11 or the Ukraine response. People fleeing Ukraine have come into a groundswell of support, from the baby strollers left at the Poland border in masse to people banding together to house refugees.

Pain is to be avoided and embraced. In the United States, the general mindset is to avoid pain at all costs. We prefer pills to processes. Yet certain pains prod us to become better, to grow, to mature.

Pain is universal and personal. It’s a universal feeling, though deeply personal to each individual. While we all experience pain, each person’s occurrence is unique. Pain carries similarities in how we speak of it but its history, breadth, and depth is singular to the person experiencing it.

Pain is complex, it’s paradoxical, and via negativa is a fair way to go about describing it; particularly given its ability to transcend words.7 Though it is commonly referred to as an external force, it is not an entity outside ourselves. It isn’t simply the physiology our nerves send to our brain. Rather, pain is an event, interweaving the body and the mind. It is a context dependent event based on the interplay of items including culture, worldview, and the meaning we ascribe to it. For instance, it has been shown that people perceive pain inputs around similar intensities, but their reaction threshold was varied. It should not be downplayed that our perceptions can influence pain sensations.

Theories of pain have evolved from the Cartesian dichotomy to the neuromatrix model which accounts for the complex array of neural inputs based on the individuality of each person and his/her environment. The threads between emotions and physical pain are so intertwined that what we perceive as bodily pain can actually be the psychological manifesting itself in the physical.

Although everyone is touched by pain, we do not have to be solely defined by it. Humanity can influence pain and amalgamate the shards into something redemptive. This process in no way takes away from the woes of pain on Planet Earth. Pain primes us to act - both for ourselves and others.

Remember Joseph Townend and his agonizing pains? His story didn’t end there.

“Finally, are you afflicted, poor, distressed, with the ills of life? Endure a little longer, hold fast the beginning of your confidence, look to the strong for strength,

‘And watch a moment to secure

An everlasting rest.’ Amen”

- Joseph Townend

He recovered, married, became Reverend Townend and moved to Australia for nearly twenty years before returning to the United Kingdom until his death in 1888 at the age of 83.

Author’s Note: This post was influenced in large part by Joanna Bourke’s book, The Story of Pain, which looks at how people in Britain and America communicated and interpreted pain from the 1760s onward.

This isn’t to say people did not self-medicate. After all, prior to ether and chloroform, which were invented in the mid-nineteenth century, pain relief was sought in substances like opium, alcohol, and salicylate (willow bark).

Trust me, it’s much less woo woo than it sounds once you dive into it. For a great explanation on somatization and its relation to trauma, definitively read The Body Keeps the Score

It’s also why studies have shown that we are better able to give advice to others than ourselves. Putting distance between ourselves and feelings/events/objects engenders more objective thinking. If you are struggling with what to do, one suggestion is to ask yourself what you would say to a friend in that same situation.

The most psychologically healthy people have a high sense of coherence in their lives - “The more a person is able to understand and integrate (comprehensibility), to handle (manageability) and to make sense (meaningfulness) of an experience or disease, the greater the individual’s potential to successfully cope with the situation or the disease.”

Via negativa is also called the Apophatic Way (apophatic comes from the Greek “to deny”). This way of thinking was particularly prominent in the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius and Moses Maimonides and generally most associated with these two. However, it appears that Neoplatonic philosopher Proclus originally came up with the term - “negations are truer than assertions”. Pseudo-Dionysius, a sixth century Christian mystic spoke to this way of thinking in his writings. He thought God was a being beyond any naming or human knowledge. Moses Maimonides, a twelfth-century Jewish philosopher, was one of the great translators of Aristotle. His belief was the Torah provided an imperfect description of God and that the best way to describe God is through silence. If one must describe God, it is preferable to state what He is not rather than attempt to encompass what He is.

Loss aversion is not as prevalent in smaller amounts as in larger wagers. Further, some believe what we attribute to loss aversion is actually simple psychological inertia (eg the tendency to maintain status quo).

The proficient use of metaphors to describe pain speaks to the transcendent qualities of pain. It doesn’t merely hurt, it feels like a drill in the back of your eye; it feels like a thousand pounds of pressure; it presents itself as a flash of red in a sea of grey. It burns, sears, scalds, boils, tears, rips, etc.