This is the first of several posts that discuss mimesis and its impact on our lives. Mimesis is the process of imitation. It comes from the Ancient Greek term mīmēsis and originally referred to making works of art that matched models of beauty, truth, and goodness. Plato drove the shift towards mimesis being discussed in the literary realm. Both terms use mimesis to portray aspects in the natural world.

First, we’ll delve into a basic explanation of the mimetic theory of desire, its criticisms, and how the stock market displays mimetic behaviors. If you’re already mimetic theory fluent, scroll to the bottom for its shortcomings and its stock market manifestations. Subsequent posts will cover why Girard thought Christianity is the best antidote, cancel culture as the new human sacrifice, social media’s internal mediation, and the impact of mimesis on Peter Thiel.

The man behind mimetic theory: René Girard

Girard’s inspiration for mimesis was formed by an early romantic relationship. In his early 20’s, he fell in love. Shortly thereafter they became an item. One day his desire for her immediately fell away. What happened? She asked him if he wanted to get married. Before long he nixed the relationship. Once she was living her life and dating other men, his desire for her became intense once again. The more she denied herself to him, the greater his want. It was as though her desire for him affected his desire for her. This was his first interaction with the hidden roles of desire and forms taken.

“I think the reason we talk so much about sex is that we don’t dare talk about envy. The real repression is the repression of envy.”

His work was multidisciplinary and primarily concerned with Philosophical Anthropology (e.g. “What is it to be human?”). Subjects he espoused on included Literary Criticism, Psychology, Anthropology, Sociology, History, Biblical Hermeneutics and Theology. Girard believed that the great modern novelists (such as Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust, and Dostoevsky) have understood human psychology better than the modern field of Psychology. Freud to him was a fantastic observer but a subpar interpreter. A crucial mistake was assuming human beings are largely autonomous, which did not correctly factor in the role of imitation.

Deconstructing the theory of mimetic desire:

Mimetic desire states we don’t want what we want because we want it. Rather, we want what others want because they want it. This leads to wanting to be the other person. Importantly, this process is subsconcious. Human desire is social in nature.

Mimetic theory in a nutshell: (1) we imitate each other’s desires and want to be them —> (2) leads to conflicts —> (3) resolution sought via scapegoat mechanism —> (4) cover-up ensues

1) Imitation

“Humankind is that creature who lost a part of its animal instinct in order to gain access to "desire," as it is called. Once their natural needs are satisfied, humans desire intensely, but they don't know exactly what they desire, for no instinct guides them. We do not each have our own desire, one really our own. The essence of desire is to have no essential goal. Truly to desire, we must have recourse to people about us; we have to borrow their desires.”

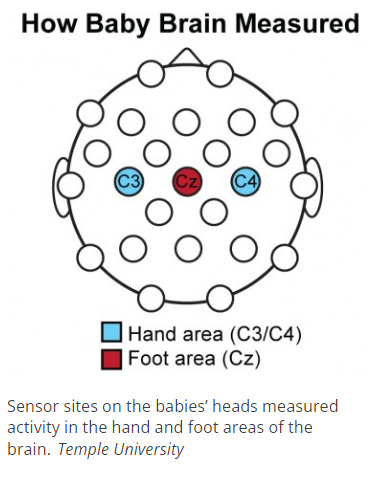

Humans are among the most proficient at imitation. It is a basic mechanism of our learning. Beginning at around 8 months, children copy simple actions and expressions of others during interactions. One study showed brain activation patterns in babies that mimicked adults. When an adult touched a toy with his foot, the “foot area” of the baby’s brain showed more activity. If the hand was used, the “hand area” of the baby’s brain had increased firing.

Indeed, our neural structure promotes imitation via mirror neurons. These are a type of sensory-motor cell that are activated in the brain when someone performs an action or sees someone performing the same action. Scientists remain divided in the wider implications of mirror neurons. Some go as far as saying that autism is a mirror-neuron system disorder. Others believe the functionality of these mirror neurons is not so special. It’s merely a general ability of neurons.

Once our basic needs are satisfied, desire moves to the forefront. Instead of satisfying hunger or shelter, it becomes about what others want. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pyramid in effect becomes inverted. We learn how to want and what to want from others. “The Romantic Lie,” is how Girard describes our belief that our desires are our own.

“We would like our desires to come from our deepest selves, our personal depths, but if it did, it would not be desire. Desire is always for something we feel we lack.”

Human desire is not individual. It’s collective. It’s social. Desire, in its essence, is contagious. Our desires are triangular in nature: there’s a subject, an object, and a mediator between the two.

“To say that our desires are imitative or mimetic is to root them neither in their objects nor in ourselves but in a third party, the model or mediator, whose desire we imitate in the hope of resembling him or her.”

The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world you merely desire stuff. The tangible as opposed to the intangible. Imitation is not about the object of our desire or the experience. It’s about the other person from whom we’ve learned to want these things – referred to as the model/mediator. Ultimately, desire coalesces around us wanting to BE. We want to inhabit their being. The true foundation of desire is the other person. These other people are what Girard calls models or mediators. Thus, our consumerist culture is a farce as object attainment will never satisfy. This helps explain the hedonistic treadmill. Our happiness levels from big events return towards the mean because the object was not our true desire. Note Girard uses 2 terms: imitation and mimesis. Imitations are positive; mimesis refers to the negative aspects of rivalry. This post will use the terms interchangeably.

Think about it: You don’t want to lead, you want to be a leader. You don’t want the Michelob Ultra, you want the status of being part of the “we drink beer yet stay in shape” peer group. You don’t merely want the supermodel, you want to be seen as desirable. You don’t want to win, you want to be a winner. You don’t want to have one-off success, you want to be seen as successful. Advertisers know this and leverage it to their advantage. That’s why we are shown other people instead of the products (e.g. naked Abercrombie models to sell clothes) – it’s about the desire for recognition, satisfaction, and status.

To be fair, objects do account for the material percentage of our daily activities and concerns. A key principle of Girard’s is that mimesis occurs in our subconscious. We focus on the object when our concern is really with the other person. Our perception of an object is determined by mediators. Think back to when you were the nerdy kid trying to fit in with the cool kids. If the cool kids like trading crypto, while the nerd think its valuation has been materially inflated by Tether’s fund flows. The kid will likely mute his true feelings and convince himself that he likes trading crypto and to HODL to the moon. On social media, the models are the influencers; those fat-tailed few with the highest number of likes and followers.

The process through which a person influences the desires of another is called mediation. When a person’s desire is imitated by someone else, he/she becomes a mediator or model. An example would be a product hawked by a celebrity – the celebrity is said to be mediating the consumers’ desires. In other words, the celebrity is inviting people to imitate themselves. The product is not promoted based on its inherent qualities but because the celebrity desires it. Do you really think people buy Cindy Crawford’s skin care line because it has Melon Leaf Stem Cell technology (whatever that is) and some French anti-aging specialist behind it? Do we truly think Matt Damon or Tom Brady know what they are talking about when they pitch crypto? Or do we want to, just maybe perhaps, be as they are?

This wanting to be things is a metaphysical desire. The object is desired only as part of a larger wanting to be the mediator. The original object of desire becomes a token representing the metaphysical desire of having the being of the model/rival – at its worst it leads not solely to rivalry but to total obsession with and resentment of the mediator. This is why the mediator becomes the main impediment in the person’s accomplishment of their “being” desire – this desire will never be satisfied as one cannot be another person. The higher our dissatisfaction with ourselves, the greater our obsession to be someone else can become.

Assessing narcissism based on mimetic desire: the model watched and strove for is not a peer but an idealistic version of ourselves that we want to be seen as. The more she works to imitate themselves, the less they success in this perfectionistic projection.

Mimetic desire leads to self-deception through lying to yourself to identify with who you think you ought to be. It is a subconscious process. Taken to its logical conclusion, this chasm between who you want to be and who you feel you ought to be results in shame rather than scrutinizing role models. “I don’t fit the picture I have of the role model so the problem must lie with me.” Subconsciously, one is thinking, “If only I could be them. All my problems would be solved.” The grass is always greener fallacy finds its fertilizer in Girard’s theory.

The distance between the subject and model is of premier importance. The closer together, the more problems arise. External mediation is where the subject and model are mediated on different planes. It’s the difference between you and the Rock. The Rock will never be your rival because he’s in a different stratosphere. Neither will Jeff Bezos ever be a monetary rival of yours.

The other type is internal mediation – you are part of the same world as your model. You end up desiring the same things, but because you are on the same plane, you become rivals. It’s the scarcity mindset in that there is not enough for everyone so “I’m gonna get mine”. As members increasingly resemble each other, the lack of differentiation generates disorders and result in a “crisis of differences”. Competition becomes the fiercest when competitors are similar.

According to Girard, the desire for any object is always enmeshed in social linkages, insofar as the desire only comes about in the first place through the mediation of the other. When the model is close to us, we subconsciously hide to ourselves and others they are our model, arousing within us jealousy. As the feelings intensify, we go to greater lengths to disguise these feelings. What initially is admiration transforms into envy. We might do things that seem out of character, like attacking the model and sabotaging them. “The closer the role model is to us, the more shame we feel as we flip back and forth between adoringly imitating them and performatively distancing ourselves from them.” Be on guard when your peer becomes a model for you as with time the relationship could become your rival.

“Imitation becomes intensified at the heart of the hostility, but the rivals do all they can to conceal from each other and from themselves the cause of this intensification. Unfortunately, concealment doesn't work. In imitating my rival's desire I give him the impression that he has good reasons to desire what he desires, to possess what he possesses, and so the intensity of his desire keeps increasing.”

Hierarchies and religions evolved in response to mimesis. Both increase the distance between people. Girard’s argument is that the origin of kings has roots in sacrificed scapegoats and became deified. In religion, there are non-peer relationships such as God, priests, and the king. The new kings of our day are business founders. Alex Danco makes an excellent point on the differentiation of founders: “In a culture where the Founder (and not CEO) is the highest-status title, there’s no point in jealously coveting your founder’s title, because it’s not something you can take. The only way you can act on that envy is to actually become a founder yourself.”

The movie All About Eve shows external mediation morphing into internal mediation. It’s based on actual events from the Broadway play (and later movie), The Two Mrs. Carrolls. Austrian-British actress Elisabeth Bergner was winning high praise for her role as Sally Morton Carroll. With the widespread acclaim, she began attracting many followers who would dress like her. One in particular was a shy, younger girl who turned up night after night to see Bergner. Bergner took pity on the waiflike woman who consistently stood outside the stage door. The girl became mentored by Bergner, who sponsored her theater career and employed her as a secretary. Berger discovered that no good deed goes unpunished, as the girl tried to sabotage her acting career and take Bergner’s husband, director Paul Czinner.

Small potatoes lead to big fights. Ironically, the smaller the issue, the fiercer the conflict and more personal it becomes. Freud called this, “the narcissism of small differences.” Remember, it’s not about the object, but about the mediator/model. If the battle truly pertained to an object, an increase in the object’s value would lead to intensification. Yet we all know someone who exerted massive energy at the menial. As Henry Kissinger famously remarked, “The battles were so fierce because the stakes were so small.”

Why is this the case? Participants are more similar in smaller confrontations. This internal mediation, or their similarity, has a higher likelihood of causing conflict because we all want the same stuff and to be seen as a certain type of person. Further, people want to cover up the true root of the fight when it comes to the small stuff. Fighting over big things carries weightier justification. I have heard of women fighting over the salad dressing that would be served at a school function. Or people becoming fascist once elected to an HOA or school board. They will repress by saying, “It’s for the community.” Or, “It’s for the children.”

We wrestle with two conflicting ideas – we have a need to have our peers recognize us as a particular type of person while ensuring no one catches you seeking this recognition. Exposure opens you up to the horrendous news that you are not the person you are trying to be. You’re a poser and summarily rejected. On FinTwit, people are trying to appear as shitposters who are also brilliant stock selectors. Some of the biggest seeming a-holes are incredibly nice in person. And then there are those who have no clue what they are talking about in the market. (However, there is just as much value in identifying these contras to position your own portfolio diametrically opposite.) Writing this has been an exercise in fighting my conscious thoughts, subconscious beliefs, and imposter syndrome. To write in any meaningful way is to be vulnerable. And, to me, the possibility of being an imposter is terrifying. Of spending precious, disciplined time only to be derided.

“We feel that we are at the point of attaining autonomy as we imitate our models of power and prestige. This autonomy, however, is really nothing but a reflection of the illusions projected by our admiration for them. The more this admiration mimetically intensifies, the less aware it is of its own mimetic nature. The more "proud" and "egotistic" we are, the more enslaved we become to our mimetic models.”

Imitation leads to —>

2) Conflict

“If we ceased to desire the goods of our neighbor, we would never commit murder or adultery or theft or false witness. If we respected the tenth commandment, the four commandments that precede it would be superfluous.”

A body of people wanting the same, finite items inexorably leads to conflict. Rivalries develop for the same resources. Mimetic desire leads to mimetic rivalry and then to mimetic violence. Blood feuds and duels are prime examples of mimetic violence. These were considered legitimate legal instruments and functioned as an effective form of social control for minimizing or ending conflicts between those related by kinship.

“Rivalistic desires are all the more overwhelming since they reinforce one another. The principle of reciprocal escalation and one-upmanship governs this type of conflict. This phenomenon is so common, so well-known to us, and so contrary to our concept of ourselves, thus so humiliating, that we prefer to remove it from consciousness and act as if it did not exist. But all the while we know it does exist. This indifference to the threat of runaway conflict is a luxury that small ancient societies could not afford.”

A blood feud is a cycle of retaliatory violence – a perpetual vengeance between families. It’s an extreme outgrowth from protecting one’s honor and is more prevalent in honor-shame cultures. Girard would see this as each family mimicking the other’s aggression, leading to the violence spiral. The rise of the modern justice system has mediated this runaway violence through the court system and use of law enforcement. Where the justice system is weak, blood feuds remain.

Blood feud in other languages:

Albania: gjakmarrja

Montenegro: krvna osveta

Japan: katakiuchi (敵討ち)

Philippines: rido

Conflict often manifests as the pursuit of status. Mimetically, status equates to being. Status can also mean being part of a group. It’s common to hear of status as a zero-sum game. I tend to think of it as a power law. A few people are the winners while the vast majority are losers. It can be perceived as zero-sum if you think someone’s losing is your gain and vice versa.

As mimetic desire is triangular, so too is conflict. Conflict isn’t two-dimensional but three-dimensional. Two-dimensionality is the hero’s journey as enunciated by Joseph Campbell. The hero (e.g. knight) wants a goal (e.g. princess in a castle) but is being thwarted by the obstacle (e.g. dragon). The crucial leverage point is between the hero and the obstacle. This Hero’s Journey is the common story template we see in literature and movies.

In three-dimensional conflict, the leverage point is between the hero and their ideal (model/mediator). The hero wants to become the ideal and the way this is done is by mimicking the model. Typically, what the hero wants is intangible: status, respect, power, love, and admiration. That is, to be seen as a certain type of person, feel like that person, and enjoy the adulations of that person.

Conflict leads to —>

3) Scapegoating

Groups single-out an individual or problem as the headwaters of their issue and violently expel/eliminate this member, leading to communal peace and restoration. This poor soul used in an attempt to break the violence cycle is the scapegoat. It restores differentiation - social differentiation and order are derived from the scapegoat mechanism. Importantly, the scapegoat is no guiltier of acts than other members of the community.

Girard subscribed to the paradox that the violence problem typically can be solved with a smaller dosage of violence. People who were formerly at loggerheads now unite together against the scapegoat. The process is subconscious: the victim is never recognized as an innocent scapegoat. Instead, the victim is construed as a monster that transgressed some law/prohibition and deserves to be punished. The community deceives itself into believing the victim is the antagonist and elimination restores peace. Prior to Christianity, an innocent scapegoat was an oxymoron.

Girard believed scapegoating was an efficient mechanism to restore peace and helped in the civilization of man (rather than rational deliberation). Only one man can be the king, but everyone can share in the persecution of a victim. This is not to say that it is perfectly efficient – only that it has helped historical human communities maintain social peace.

Who is the ideal scapegoat? Someone not involved in the conflict and as such is innocent from the crimes they are accused of. If the scapegoat were not neutral, either side would interpret the killing as a response demanding an equal reaction. It de-pressurizes the situation. Indeed, the initial peace from the scapegoat sacrifice can be so euphoric that it takes on religious overtones. The victim is consecrated inasmuch as the death brings forth peace and restores order.

“Human culture is fundamentally and originally religious, rather than secondarily and supplementally.”

All cultures are founded upon some sort of religious basis. The function of the deities/the sacred/God is peace in the community. This ensures scapegoating will be administered by means of the religion. The earliest cultural and religious institutions take the form of rituals. A ritual is a reenactment of the original scapegoating murder. The most popular ritual is sacrificing. When a ritual killing occurs the community is commemorating the original event that promoted peace. Once the victim is eliminated, a “prohibition falls upon the action allegedly perpetrated by the scapegoat.”

Scapegoating leads to —>

4) Cover-up

After the scapegoating process has completed, the cover-up ensues. It’s how communities and cultures overcome internal strife. Taboos, prohibitions and other laws are enacted to prevent further violence. This founding murder is enacted over and over again as a means of catharsis. Again, this occurs on a subconscious level.

Myths are the narrative outcome of rituals. Girard thought that all myths were founded upon violence. If there were no violence, it was because the community struck it from the record (“covered it up”). Persecution texts recount collective violence from the persecutor standpoint. History is written by the victors. Witch hunts, lynching, and persecution of Jews are given as modern equivalents of myths.

Ending thoughts on mimetic theory:

This post (and nearly all of what is written) focuses on the negative aspects of mimetic desire. An important piece of information to file away is Girard did not believe mimetic desire only produces evil:

“it can become bad if it stirs up rivalries but it isn't bad in itself, in fact it's very good, and, fortunately, people can no more give it up than they can give up food or sleep. It is to imitation that we owe not only our traditions, without which we would be helpless, but also, paradoxically, all the innovations about which so much is made today. Modern technology and science show this admirably.”

Interestingly, he did not take up this beneficial aspect of mimesis until later on in his career. Positive mimesis affords the possibility that all aspects of culture are not undertaken via scapegoating.

“Mimetic desire enables us to escape from the animal realm. It is responsible for the best and the worst in us, for what lowers us below the animal level as well as what elevates us above it. Our unending discords are the ransom of our freedom.”

Mimesis is antithetical to radical acceptance. Mindfulness comes from radical acceptance. It’s accepting what is out of your control and looking through the lens of non-judgment. Mimetic desire tells you that you’re never enough. If only you gain this or be that, then you’d be whole. It operates on our subconscious – once it is brought to consciousness the breaking of the spell can begin.

Whoever your models are have a massive impact on your life. Pick the right models that align with your values. To figure out what your desires are, think back to your childhood and to your values. If one of your values is self-respect, but you are consistently a yes-person, someone who returns emails 24/7, or have problems saying no, then it’s clear you are desiring some other end by which your actions are the means.

If you’re like Rod Stewart and love playing with model trains in your free time, then by all means do it. Rod Stewart loves building model railways so much that he booked an extra hotel room touring to play with them. The school system and society work hard to crush our individuality. Thinking back to we weren’t inhibited by others is a way to recover joy.

Criticisms:

Categorizing all desires as mimetic is an overreach. The theory explains many desires, but not all of them. Critics say that the existence of taboo desires, like homosexuality in repressive societies, are hard to explain using this theory. Also, situations come with many possible mediators, so the person has to make a choice among them, which allows room for some authenticity in the choice. Girard doesn’t appear to adequately account for innovation; that is, the first person to start the trend…who are their models?

Girard presented the view as being scientifically grounded. Certain anthropologists have contested some of his claims. His readings of various biblical, myth, and literary texts have also been called into question. Thus, some scholars have posited his writings are not scientific but metaphysical. Other critiques have been based on his Christian worldview – from his interpretations to the fact this was the lens through which he viewed the world.

René Girard may have not been the first to suggest desire was mimetic, though he seems to be the first to say that all desire is mimetic. Gabriel Tarde, Francois Duc De La Rochefoucauld, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza and Alexis de Tocqueville referred to mimesis.

“By the very fact that we conceive a thing, which is like ourselves, and in which we have not regarded with any emotion, to be affected with any emotion, we are ourselves affected with a like emotion (affectus).” – Benedictus de Spinoza

“The same equality that allows every citizen to conceive these lofty hopes renders all the citizens less able to realize them; it circumscribes their powers on every side, while it gives freer scope to their desires. Not only are they themselves powerless, but they are met at every step by immense obstacles, which they did not first perceive.” – Alexis de Tocqueville

“And therefore if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies; and in the way to their end, (which is principally their own conservation, and sometimes their delectation only,) endeavor to destroy, or subdue one another.” – Thomas Hobbes

A criticism I have not encountered elsewhere for Girard rests upon the principle that sameness (internal mediation) leads to conflict. Karen Stenner is a political scientist specializing in authoritarianism. Her argument is that predispositions to obedience and conformity, or what she calls “oneness and sameness”, lead to conflict in intolerant individuals. Authoritarians want differences restricted regardless of the circumstance and no matter the social cost. Much of racism is better understood as “difference-ism”. In other words, authoritarians are intolerant of differences. And the more we force them to celebrate differences, the more we guarantee their “manifestly intolerant attitudes and behaviors.”

“But all the available evidence indicates that exposure to difference, talking about difference, and applauding difference—the hallmarks of liberal democracy—are the surest ways to aggravate those who are innately intolerant, and to guarantee the increased expression of their predispositions in manifestly intolerant attitudes and behaviours. Paradoxically, then, it would seem that we can best limit intolerance of difference by parading, talking about, and applauding our sameness. [...] This strategy is not nearly as daunting as it might sound, as it is the appearance of sameness that matters, and that apparent variance in beliefs, values, and culture seem to be more provocative of intolerant dispositions than racial and ethnic diversity. What is daunting is the fierce resistance that such proposals encounter from those very actors with the greatest stake in promoting tolerance and respect for difference. But blind faith aside, the science of democracy yields some inescapable, if heretical conclusions. Ultimately, nothing inspires greater tolerance from the intolerant than an abundance of common and unifying beliefs, practices, rituals, institutions, and processes. And regrettably, nothing is more certain to provoke increased expression of their latent predispositions than the likes of “multicultural education,” bilingual policies, and non-assimilation. In the end, our showy celebration of, and absolute insistence upon, individual autonomy and unconstrained diversity pushes those [who are] by nature least equipped to live comfortably in a liberal democracy not to the limits of their tolerance, but to their intolerant extremes.”

Mimetic desire and the stock market:

In the short-term the market is a mimetic machine. In the long-term, it follows the fundamentals. Look no further than the crowding into the most popular, largest stocks, like FAANG. The percentage contribution to market returns has remained considerably elevated versus long-run averages.

No one gets fired holding the biggest names. It’s the same song, different verse of “Nobody ever got fired for holding IBM,” which had been around since the 1970s.

Sell-side likewise falls prey, with only 5% of S&P 500 stocks being “sells”. It’s much easier to preserve lucrative C-suite access and sweet banking fees by expressing reservations with a “hold” rating. Studies have shown that sell-side analysts herd around similar recommendations, and display an increased willingness to stand out when it comes to upgrades as opposed to breaking away from the crowd with downgrades.

Before Meta’s disappointing quarter, 84% of analysts had a “buy” rating across 62 analysts. Only 2 analysts (both in Europe) dared to stamp it with a “sell” rating. A recent Bloomberg article speaks to these “two psychological pitfalls” that sell-siders face:

“One is the idea that a stock that’s gotten this far will likely keep on climbing. The other is when everyone else has a “buy” projection, it’s safer to advise something similar. “Facebook has been one of Wall Street’s darlings, and no one has wanted to stand up and say that something has changed,” Weitzel says. “Why does anyone follow the herd? It’s harder to go against the grain.” As the economist John Maynard Keynes observed, it’s often better for one’s reputation to “fail conventionally.””

It’s easy to become complacent when stocks show momentum and people are crowding into the same stocks. Instead of being a buy indicator, it’s more often cause for concern. As this period grows more distended, the window for continued outperformance narrows. Another way to state it is as the exposure period lengthens, the opportunity lessens. For example, stock market seasonality doesn’t work anywhere like it used to because the alpha has been arbitraged away. It’s the same thing with traditional value metrics like low P/B and P/E.

Meme stocks and crypto are two other prominent examples of mimetic desire we see in the markets. Stories are made up in an attempt to explain why they are buying, when it really comes down to desiring it because other people want it. Wanting it because others are supposedly getting rich off of crypto and meme stocks, so why should you miss out? FOMO, or the fear of missing out is an unheralded, critical driver behind mimesis. No one wants to miss the next, big thing.

Speaking of which, it's been eye-opening to see certain, battle-hardened value investors convert into crypto cheerleaders, FAANG fiends, or “we remain value investors – it’s only our definition of value that’s changed”. I’m convinced this is a late cycle indicator and indicative of FOMO capitulation. Similarly, short sellers abdicating shorting was a great sign we were near the top. Value investing isn’t dead – it simply hasn’t yet been resurrected.

Mimetic desire is likely a key reason why momentum investing works (that is, until it doesn’t). An example would be buying stocks that are at 52-week highs and sell them when they hit a multi-month low. Winners continue to win. Momentum investing is a power law, where outsized benefits accrue to a few. Research has shown it is a good strategy until it breaks.

People (and quantitative trading strategies which still receive human input) see something working for others and want their share. Strength begets strength and desire begets desire. This isn’t to say there are no logical reasons for investing in these companies. Rather, often what we ascribe to our rational, enlightened self is tinged by post hoc analysis. We see this daily in new stories telling us why stocks were up or down on any given day.

Technical signals are predicated on momentum. My best guess of why technical analysis works as well as it does is because at the margin, material stock market flows believe it will work (i.e. becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy). It’s not that there’s some magical property inherent in a head and shoulders pattern.

And in fairness, technical analysis is probabilistic and, like momentum, is not 100% explained by mimesis. But mimetic desire is present in its own way. Look no further at how hard it is to zig when others zag, to bet on something that is contrarian, to be a short-seller where day after day the market is screaming at you that you’re wrong….until you’re right.

Great article Stacey! The Financial Times sent me your way, which in my world is the highest form of praise

Hi Stacey, thank you for writing this! Very thought provoking.

I can say without any doubt that as a former "scapegoat" myself, your thoughts are particularly helpful. (I worked in Big 4 audit, was the Group Head's favored employee (hired directly by him), this dynamic slowly led to intense rivalry / deliberate sabotaging / nasty treatment from middle managers and even certain partners who desired the Group Head's admiration, eventually I didn't want to put up with the toxic culture anymore and left.)

In particular, I like how you married the concepts of mimetic desire and the act of investing itself. Thiel combines mimesis and business differently (e.g., extreme competition leads to businesses just copying one another, buying the same CAPEX, trying to hire the same 'star' employees, going after the same markets, etc.). But I never really thought of the fact that investment management is itself a business and, as such, exhibits the same tendencies.

This reminds me of Bill Ackman and Mohnish Pabrai being Buffett/Munger fanboys, going to Berkshire annual meetings and asking very specific questions about how they ran their initial partnerships, etc. (footage of their questions can be found on YouTube.) Their desire is very real and palpable. Interestingly, in answering their questions, it's almost as if Buffett/Munger find their desire repulsive/perverse. I could be misreading them...

As I was reading your article, it also occurred to me that one could identify mimesis in relationships of high cooperation (i.e., student-mentor). You point out Girard's belief that mimetic desire contributes to progress in modern technology and science. I'd be curious to know how this sort of cooperation doesn't end up in violence / scapegoating.

It would also be interesting to test the hypothesis that high cooperation is predictive of violence/scapegoating. Perhaps it's too difficult to place any quantitative value on such a relationship, so you're left with more of an intuitive sense that this is true.

Ok I'll shut up now.

(Btw I'm a big fan of Jonathan. IMHO he is much smarter than anyone gives him credit for, his insights are very well-informed, and he is truly one of the great investment analysts around. And here I am ironically confessing my mimetic desire...)