It’s not unusual for investors and investing pundits to say they do not make forecasts. As Yogi Berra quipped, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” Complexity and uncertainty waylay us all. It’s easy to ridicule those who make forecasts and look foolish in hindsight.1 Yet to cast them entirely aside is like throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

On a first principles basis, how can you act without making assumptions about the future? To live, we must make assumptions about the future and act upon them, whether professionally or personally.

Pundits make valid points about forecasting deficiencies. I don’t disagree with them, as the issues raised are valid. We are on the same team. There can very well be the illusion of knowledge.

At the same time, there can be the illusion on knowledge in their viewpoint, which lies in the belief that, because predictions are inherently uncertain and very well wrong, it is better not to make them at all.

Even Howard Marks, perhaps the most well-known critic of forecasts, makes investing assumptions. From his 1993 memo:

Instead, we will continue to try to "know the knowable" -- that is, to work in markets which are the subject of biases, in which non-economic motivations hold sway, and in which it is possible to obtain an advantage through hard work and superior insight. We will work to know everything we can about a small number of things…rather than a little bit about everything.

Convertible securities, high yield bonds and distressed company debt are all markets in which market inefficiencies give rise to unusual opportunities in terms of return and risk. We will continue to exploit these opportunities in a manner which is risk-averse and non-reliant on macro-forecasts.

Everything is a prediction

Forecasts are not merely a binary, A/B switch. They are an integral part of being human. The argument can be made that everything is a prediction.

Our brains have been called “prediction machines” or a “prediction organ”. We literally live in the millisecond past. On average, it takes 400-500 milliseconds2 for us to respond to visual stimuli. By comparison, an eye blink is 300-400 milliseconds.

Ever wonder why you can’t tickle yourself? Your brain predicts the tickling sensation and mitigates the response. In other words, there is no surprise factor, as your cerebellum knows where the sensation will occur.3

In baseball, the ball is whishing past home plate too fast for the brain to compute and act on instantaneously. Baseball players compensate for these delays by anticipating the future position of the baseball in space and acting in real-time on a future event.

You behave in certain ways due to future expectations. If you’re concerned about income levels, you are less likely to make big purchases today. You get a degree in a certain area because you expect to get a job requiring a similar sets of skills. No one gets married because they think it will make them miserable. Even idiots don’t buy a stock because they believe its value will go down.

If you’re an investor, you are relying on forecasts. Doesn’t matter if your bottoms-up and never think of macro. The predictions have merely moved from explicit to implicit. Discounted cash flow, multiples, supply/demand analysis, competitive dynamics, and the persistence of ROIC all deal with assumptions.

The question is not “to forecast, or not to forecast”. Rather, it’s about crafting predictions that cushion our weaknesses and play on our strengths.

A general framework

The best forecasts hold loosely to their assumptions. If anchored to anything, it’s to common sense. The only certainty about predictions is that they will change. And when the facts change, they change.

Good predictions assume different outcomes. They constantly work on deciphering noise from news. History is like a La Croix in that it has the sneeze of a hint of repeating itself, but never fully rhymes.

As Michael Mauboussin describes in Expectations Investing, there are a few items that drive companies’ results. The key is to ascertain what the stock is pricing in (“the expectations infrastructure”), and if you have a materially divergent opinion.

Perhaps the same is true looking at the bigger picture. Interest rates and stock market valuations are often tied to assumptions investors make about inflation and growth. As such, a better way to forecast would not be to call for a specific economic situation to happen, but to have an action plan based on varied events. In this way, you’re not wedded to your predictions.

Of course, you almost certainly miss the inflection point, but you’d have missed it anyways! Correctly trying to call the inflection point is a fool’s errand. The idea is to get in/out shortly thereafter, thus preserving much of the upside (or limiting much of the downside).

The initial call is not as important as subsequent actions

“It’s not whether you’re right or wrong, but how much money you make when you’re right and how much you lose when you’re wrong.” - George Soros

You don’t have to hit the bull’s eye every time to be successful. Lee Freeman-Shor’s book The Art of Execution found that investors were right about half the time on their best ideas. Some of these managers were successful only 30% of the time. Yet almost all of them still made money!

Importantly, what mattered was not so much the initial pick, but their response(s) after buying a position. For example, when facing losses, some had a stop loss limit after a certain percentage move against them, while others kept buying and reduced their cost basis.4

Forecasting, like life, is never perfect. I don’t know what inflation, Central Banks, Liz Truss, or Putin are going to do. Neither do you. What I can construct are action steps to take in reaction to certain events. I can sketch out rough probability levels to help me weight purchases. I can be willing to seek out and sit with disconfirming information, with paradoxical data, instead of making knee jerk reactions.

Beware information overload

Your brain has not evolved to take in the firehose of data overflowing from every website orifice. Do you want to be happier? To you want to make better decisions? Read less noise. Good forecasts cut the noise and focus on the critical components. Do you really need to check the news several times a day?

More data does not lead to improved decision-making. It actually worsens it, because you become overconfident.

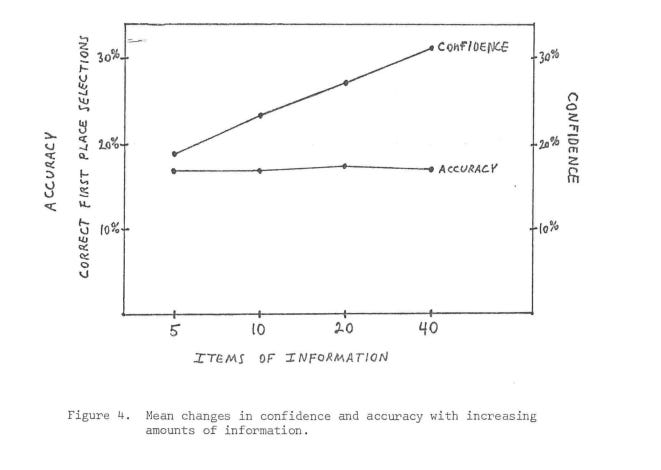

A famous study looked at veteran horse racing handicappers’ predictions of 40 horse races spaced over 4 rounds. There were 10 horses in each race, meaning a random bet is right 10% of the time.

At first, participants received 5 pieces of information per horse to predict the winner. They also had to rate their confidence in the chosen outcome. With limited information, handicappers were 17% accurate, or more than twice what randomness would result in. Their confidence level was 19%.

In subsequent rounds, more information was provided. For example, in round 2, 10 pieces of information were disclosed. This went up each round to ultimately end in 40 pieces of information in the final race. Higher data availability did not impact accuracy, which remained at 17%. What did change was participants’ confidence levels, which nearly doubled to 34%.

Conclusion

It’s easy to get locked into an unmalleable forecast. We rely on single factors to try to explain complex phenomenon. (Similar to how science tends to focus on a single cause as evidenced by seeking gay or autistic genes.)

However, prediction problems do not mean forecasts in and of themselves are worthless. It is literally impossible for humans not to forecast, as it makes us who we are. Proper predictions have helped engender our survival.5

Good investing assumptions are flexible and consider multiple outcomes. As the facts change, we can change our minds. They leave space for the wide gaps in our comprehension, for those unknown unknowns and known unknowns. On the other hand, they capitalize on “know[ing] the knowable”. They minimize the inputs while maintaining maximal outcomes.

You don’t necessarily have to bull’s eye the future to be successful. In shorting, instead of calling for a growth story breaking, anecdotally I’ve found it of more use to wait until the breaking point and then put on a position. The downside is such that you can still come out a big winner.6

Compared to trying to predict the future, having a plan for what to do across different situations is likely a better option. Further, having a game plan for successive actions after the initial investment is of high importance.7

Or, conversely, to get a big call right once and then see future out of consensus calls fail to pan out. There’s a graveyard of people who got it right once and have since failed to recapture lightning in a bottle.

1 millisecond = 0.001 seconds; 500 milliseconds = half a second

On a related note: If you want to go down a rabbit hole, check out Friston’s free-energy principle theory. It posits that all life is predicated on minimizing the space between your expectations and sensory inputs. The theory “says that all life, at every scale of organization—from single cells to the human brain, with its billions of neurons—is driven by the same universal imperative, which can be reduced to a mathematical function. To be alive, he says, is to act in ways that reduce the gulf between your expectations and your sensory inputs. Or, in Fristonian terms, it is to minimize free energy…Free energy is the difference between the states you expect to be in and the states your sensors tell you that you are in. Or, to put it another way, when you are minimizing free energy, you are minimizing surprise.”

For more details, I recommend Gavin Baker’s book overview. In itself, the book is a short, easy read that is worth the small time investment.

So far.

Plus, you miss out on the negative returns from incorrectly calling a growth story to break or calling it too soon so the stock continually grinds against you.

Author’s note:

“Extremes dominate our world and we think they are the norm.” - Terry Burnham and Jay Phelan

An overarching theme society is running into time and time again is reductionism. We live in a world dominated by materialistic, binary views. You’re either with us or against us. If you agree with me and my values than you love this country. If you don’t, you’re the enemy.

You can make forecasts and be wrong and look foolish or act like you don’t make forecasts, not look foolish to others, and still be wrong.

It’s integral to look at the whole, the gestalt. Gestalt is when the sum of the parts is greater than the whole. Complex systems demonstrate this in spades. Our cultures are losing context, which is a slippery slope. Many things we try to fit into tight, neat boxes in fact occur on spectrums.