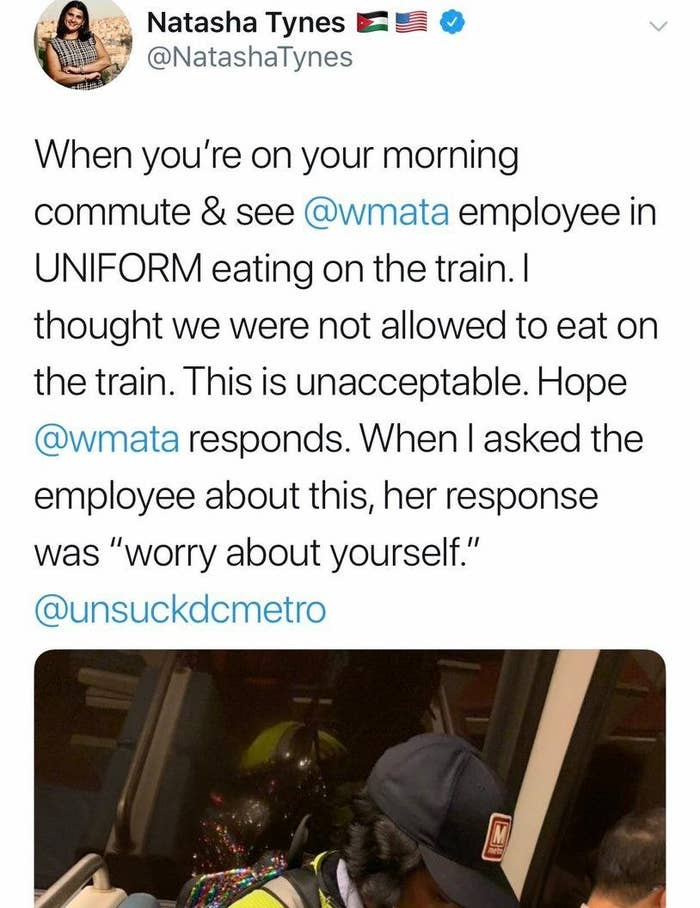

With one tweet, it was all gone. The years of hard work on her book deal. Her multi-decade career. Her ability to help support a family of five.

She removed the tweet within 40 minutes, but the backlash could not be undone. Her book deal was cancelled, with the distributor saying, “Natasha Tynes…did something truly horrible today…Black women face a constant barrage of this kind of inappropriate behavior directed toward them and a constant policing of their bodies…we have no desire to be involved with anyone who thinks it’s acceptable to jeopardize a person’s safety and employment in this way.” Her publisher made similar comments. Ironically, her book “deals with issues of immigration, race and the need for belonging in a new land”.

It didn’t matter that she herself is a minority woman. Not only that, she is an immigrant. She was born in Amman, Jordan, and moved to the U.S. in her late twenties. Details don’t matter in cancel culture. Nor does one’s humanity. People yearn for sacrifices, and social media platforms provide an efficient means of execution.

“Cancelling” refers to withdrawing support from an individual, their career and popularity because of something unacceptable that was done or said. It isn’t simply unfollowing or moving support elsewhere. In theory, it’s a boycott and ensuring this person is not able to benefit from their privileged position. In practice, it’s a brutal attack on their being with the intent to destroy. It’s mob mentality.

“In a society that has fallen prey to anarchy the voracious appetite for persecution feeds on victims indiscriminately, as long as they are weak and vulnerable. The least pretext is enough. No one really cares about the guilt or innocence of the victim.” - René Girard

In Mandarin, there’s a term called renrou sousou yinqing (人肉搜搜引擎) – or human flesh search. It’s an online vigilante system where people are doxed. Social media photos showing someone misbehaving is the witch hunt catalyst. The Chinese term has been around since 2001 and describes searches powered by humans rather than computers. Initially, Mop (Chinese entertainment forum) would crowd-source entertainment trivia from users based on questions posed. Over time it evolved into requesting web citizens (wangmin) or web friends (wangyou) to come together as a quasi-detective agency to dig up information on perceived wrongdoing. Human flesh searches have been aimed at anyone from adulterers and corrupt officials to animal abuse, amateur pornography producers, and so-called unpatriotic citizens.

To quickly review Girard’s desire of mimetic theory, we don’t want what we want because we want it. We want what others want because they want it. This leads to wanting to be the other person. The process itself is subconscious. Human desire is collective, not individualistic. Our desires are triangular in nature: there’s a subject, an object, and a mediator between the two. Our sameness leads to conflict. Homogeneity increases the probability of mimetic fights. Increased distance and differentiation between the subject and the mediator offer more stability. Conflict often manifests as the pursuit of status. Mimetically, status equates to being. Status can also mean being part of a group. For a deeper dive, read the initial post in this series: Mimetic desire and the stock market.

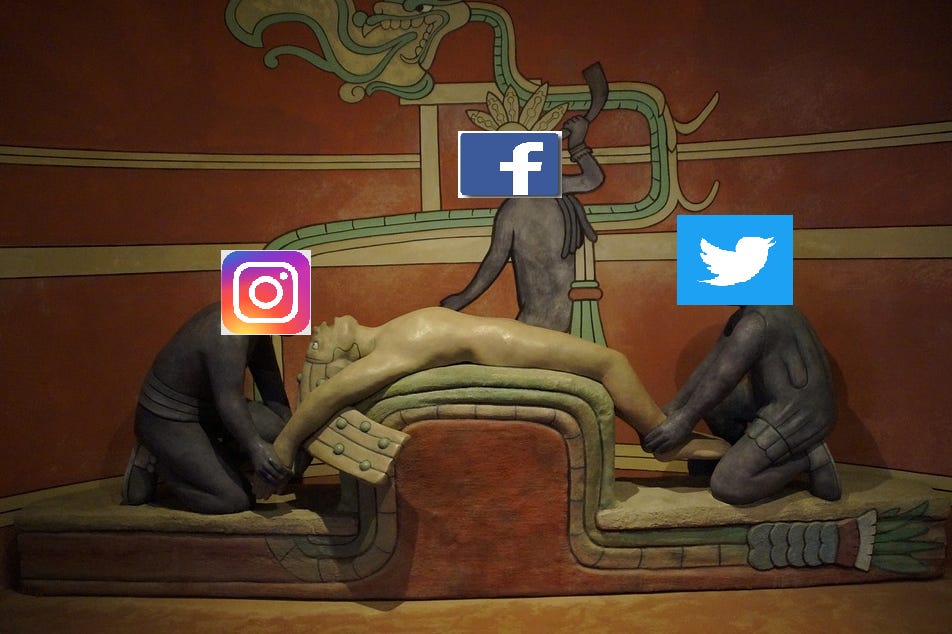

Viewing this theory through the lenses of Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, photos and videos are transient objects. The models are the people. The object in this case represents the model. Here’s the new wrinkle: mediation does not have to occur via a person. These platforms mediate the presentation of our desires. Social media has shifted popularity to followers, likes, retweets, and comments. The accumulation of popularity leads to these objects becoming increasingly mediated and as a consequence, desired. The fantasy of reaching some sort of self-actualization is projected onto a high follower count. No wonder the majority of Gen Z would like to be an influencer. It’s a reductionist version of the mass media celebrity.

Speaking of mimetic desire and media: One could view school shootings through the lens of mimesis. As shootings have become (very sadly) more commonplace, media coverage has likewise increased, and we have seen higher and higher mass shooting events. The 2021-2022 school year has already seen 141 campus shootings through February 6th – more than at any one time in the prior decade.

It is a vicious feedback loop: more school shootings and higher media coverage have an increasing impact on the number of events. Of course, this isn’t the only leverage point in the system, but many researchers believe it is a positive feedback loop. Much of the public has become desensitized to the violence; except for the subjects engaging in mimesis.

“When someone engages in a behavior, there is a probability that someone else may do the same” (Meindl & Ivy, 2017, p. 368). Often, “copycat” behavior is influenced by media sources, especially social media. Extensive coverage of mass shootings on these platforms allows potential criminals to identify with a criminal act, leading them to feel they need to fulfill a personal calling (Meindl & Ivy, 2017).”

“Researchers have also found that shooters are attracted to media’s ability to easily facilitate fame. The combination of the narcissistic tendencies of these shooters and heightened media coverage seems to have assisted in the increase of these crimes. According to Bushman (2017), “in today’s digital age, one does not have to wait for the FBI or New York Times to release the manifesto. One can easily find the manifesto on the Internet, such as on YouTube or Facebook” (p. 8). Lankford found that shooters today receive the equivalent of several million dollars’ worth of earned media coverage for their acts. Data suggests that shooters have even planned their attacks during certain months because they knew there was an opportunity to gain more attention (Lankford, 2018).”

The above citation comes from a paper theorizing about “media contagion”. The “theory is fairly new and has come to relevance within the 21st century.” The name may be new given the rise of social media platforms, but its origin extends back eons. If prostitution is the world’s oldest profession, wanting what someone else has must be the world’s oldest desire.

Mimetic desire devolving into violence and scapegoating on social media is a feature, not a bug of these platforms. Cancel culture has always existed. The lyrics may be different but the bassline is the same. In ancient times, people were cancelled through killing. However, our society is much more sophisticated. We kill the soul and claim nobody was hurt because the body is left intact. Cancel culture magnifies our binary thinking. You’re either for us or against us. There is no room for gray. The rule of law diminishes into mob-like mentality. Certainly, the law is not perfect, but neither does it mean the current situation is any fairer. Girard would say these in-groups reach a certain point of sameness that naturally leads to rivalries, resentment, and the need for a scapegoat. Members of groups can ignore their own shortcomings and laser target onto the out-group’s behavior.

Social media incentivizes cancel culture behavior through reduced friction and distance. These platforms lower barriers to connect with others and are a feedback loop for confirmation bias. The algos give you more of the content you view and like. It’s an echo chamber. With decreased distance we now are everyone’s peer. To put it in Girard’s terms, we are each other’s internal mediators. Back in my grade school days, to reach others one had to use snail mail. My 3rd grade class wrote letters to celebrities and politicians. There were books devoted entirely to listed contact addresses. One of the letters I wrote was to President Bill Clinton asking for great white sharks to be protected. It was patently clear this was external mediation - the distance between us was maintained. Nowadays, we can reach politicians and celebrities instantaneously with the click of a button. External mediators – those that magnify the distance between us – now take the form of a quasi-internal mediator. The decreased distance makes us feel as though we maybe, just possibly, could be them.

Reduced friction means it is easier for the first stone to be thrown and the subsequent pile on by others. The first stone is the catalyst for mob behavior that is mimetic. As the Bible says, “Let him who has the lowest threshold cast the first stone.” It is also the most difficult as there is no model to imitate prior to this action. The greater the number of instances/models, the easier subsequent actions. Decreased friction becomes two sides of the same coin: it makes it easier to engage in mob behavior to purge people from the out-groups and also to display loyalty to in-groups.

“To escape responsibility for violence we imagine it is enough to pledge never to be the first to do violence. But no one ever sees himself as casting the first stone. Even the most violent persons believe that they are always reacting to a violence committed in the first instance by someone else.” ― René Girard

Sociologist Mark Granovetter proposed the threshold model of mob behavior necessitates at least one individual in a crowd with low thresholds to engage in risky or aberrant behavior. Once they commence the process, individuals with initially less predisposition (higher thresholds) are more likely to engage in the same behavior. The higher threshold people have a model to follow, whereas the lowest threshold people are least in need of a model. As it pertains to social media, Geoff Shullenberger argues that rewards are attached in the form of likes and followers. In the attention economy, those who garner eyeballs can reap the rewards of viral fame.

The rise of modern judicial systems attempts to resolve community conflicts through neutral mediation mechanisms according to Girard. However, social media lacks the checks and balances seen with justice systems or with ritualized mechanisms in earlier societies. Thus, reciprocal hostility and temporary pacifications arise through the scapegoat mechanism. This looks like an unending cycle of outrage mobs, doxing, and cancelling. Respite becomes increasingly brief before the next sacrifice occurs. Mark Zuckerberg has become the Supreme Court, with Meta representing the lower court system.

“The more of us that are transfixed by spectacles of victimization, the greater the revenue the platform brings in. Like a bloodthirsty god, the platform business feeds off of sacrifice.” - Geoff Shullenberger

Ancient society rituals used scapegoating as a mode of social control. The modern-day equivalent are the platform engineers. Yet the difference is they are not after control, though this is a byproduct. The main goal is money. The money is made through capturing the highest concentration of attention. We are living in a world where, “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention”. Those that dominate our attention mint the gold.

“Cause my seconds, minutes, hours go to the almighty dollar” - Lil’ Wayne, “A Milli”

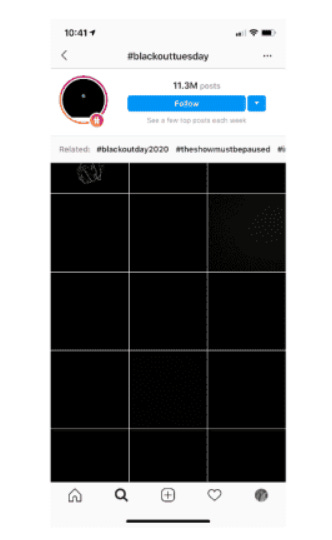

Social media allows us to feel good about something without doing anything at all. It’s the online version of a free lunch – we spend 5 seconds on a post masquerading as meaning. Take the blackout, when millions of people posted black squares on Instagram to show support for Black Lives Matters under #BlackoutTuesday. Activists on the ground say the move backfired; instead, it muffled organization. A leading organizer of BLM in New York said, “What it ultimately did is it muted the conversation. And in a time when we are trying to amplify our voices, we were inherently silenced.” The name given to these efforts is “slacktivism”.

The perverse nature of our present-day human sacrifices is the reward attached to the kill. Politicians believe they cannot win without running negative campaigns. People believe they won’t get the attention and respect they crave unless someone else is taken down. It’s the worst manifestation of zero-sum games.

The problem with cancel culture is it removes a branch rather than the root of our ills. It kneecaps constructive conversations. Did Weinstein deserve what he got? Yes, and probably then some. Has it erased the fundamental problem in our society? No. The same powerful people control Hollywood. So too is the case with Epstein – the powerful around him remain this way. Let’s face it – it is far easier to attack people rather than institutions. We feel better about ourselves. Yet attacking the person instead of the structure does not solve core problems.

Perhaps one could argue that cancelling/scapegoating helps drive momentum towards rectifying the structural wrongs. Or bringing about due process. Have the victims of these crimes been treated fairly? Has due process truly occurred? Have the ends justified the means? What about those who have been cancelled unjustly? Have they had due process? Where is the limit? Do we want today’s kids to be cancelled in the future over some dumb comment they wrote decades ago? We are more than one thing, yet too often we are treated as if our whole identity is one errant remark. We judge the speck in others’ eyes and ignore the plank protruding from our own. The best tools augment what humans are good at. The worst tools capitalize on our imperfections. Given the inherent neutrality of tools, we see both sides. The more complicated effort lies in weighing the net benefit or net detriment.

Cancel culture impedes free speech. It impedes communicative dialogue as people try to yell over each other. He who yells the loudest is not the winner. Contrary to what society tells us, simply listening to someone does not mean you agree with them. It means you are a respectful human being. We have gotten to the point where if someone says, “I identify as a boiled egg,” anything except unbridled acceptance (and enthusiasm) is deemed to be unsupportive. Cancel culture is a feedback loop that feeds on itself. Without the presence of a balance loop, its ultimate conclusion is suppression.

This conversation brings up an interesting question: how much value has social media truly created? (By value, I’m speaking in economic terms – we all know how much intrinsic “value” people derive from scrolling on TikTok or Twitter while parked on the toilet.) What have Facebook and Instagram added to productivity? Or rather, is it about what have they subtracted? Have the constant notifications on Slack or Teams helped us or merely further divvied up our attention? Seeing your family post racist comments doesn’t seem to be a productivity driver. Or witnessing someone from your high school become full-fledged Satanist. Instagram influencers have helped trash the environment and historical sites, rather than be a net positive to tourism sites (“You’re doing amazing, sweetie!”).

Twitter appears to me to be more value-added than the other networks. Yet it is plagued by the same cancel culture and scapegoating. (And its advertising prowess is nowhere close to the other platforms - A monkey throwing a dart would yield better targeting advertising.) This is to be expected given scapegoating is inherent to social media platforms. The difficulty is in netting the absolute benefit/(detraction) to society. To be fair, I come from a position where I have benefited immensely (though really only from Twitter). Networking-wise, LinkedIn hasn’t held a candle to the power of #FinTwit. Again, in fairness, being a woman in a male-dominated field that at times is capable of somewhat intelligent comments is a big help – I would have nowhere near my reach had I been anonymous.

Has Meta really created value equivalent to its enterprise valuation? (Enterprise valuation, or EV, is the minimum theoretical figure to purchase a company. It’s the total capital structure - accounting for equity, debt, cash, and minority interests.) Meta’s EV is ~$550bn, while Twitter’s is ~$27bn.

Say what you will about Netflix being in the same boat but they aren’t valued as such. The EV for Netflix is ~$184bn. In fact, except for Tencent, no media company I checked comes anywhere close to the enterprise value of Meta. Even after Meta’s recent (30%) share sell-off, it remains one of the highest valued companies on earth. Of course, a material percentage of Meta’s value comes from WhatsApp, though I would argue it doesn’t constitute enough to justify the delta between Meta and others.

At least one country agrees with the hypothesis that social media writ large does not create sufficient value for the party. Last year, China began cracking down on its tech giants. Yet it wasn’t an across-the-board suppression of technology – simply technology that was not deemed to be in the country’s best interest. (It’s true Tencent also remains one of the highest valued companies after these efforts.)

“The 14th Five-Year Plan, for example, places far greater emphasis on science-based technologies than the internet. Thus one of the effects of Beijing’s squeeze has been prioritization of science-based technologies over the consumer internet industry. Far from being a generalized “tech” crackdown, the leadership continues to talk tirelessly about the value of science and technology.

In nearly all of my letters over the years, I’ve lamented the idea that consumer internet companies have taken over the idea of technological progress: “It’s entirely plausible that Facebook and Tencent might be net negative for technological developments. The apps they develop offer fun, productivity-dragging distractions; and the companies pull smart kids from R&D-intensive fields like materials science or semiconductor manufacturing, into ad optimization and game development.”

I don’t think that Beijing’s primary goal is to reshuffle technological priorities. Instead, it is mostly a mix of a technocratic belief that reducing the power of platforms would help smaller companies as well as a desire to impose political control on big firms.” - Dan Wang’s 2021 Year in Review Letter

Compared to the resources consumed in social media, the return no longer appears adequate to China’s politburo. In the Western world, we can think about it in terms of the high salaries these companies pay, boosting competition for talent. It bumps up other salaries and diverts them away from other positions like R&D. Never underestimate the Chinese’s tenacity and willingness to sacrifice in the short-term.

As I type this post, I realize that I, too, am probably engaging in scapegoating in some form and fashion. It’s an ironic twist and something Girard would have undoubtedly predicted. Brad Slingerlend writes an excellent weekly email on things he has learned. Last week he touched on this in reference to the Joe Rogan controversary (emphasis his):

“It’s easy to scapegoat the leaders of the tech platforms for their waffling on moderation, but the reality is society is grappling with a new type of mass communication, and we are still working out the best way to co-exist with it. The extreme position of anti-moderation proponents – that we should have anarchy instead of rules and civilization – is as childish as overzealous cancel culture… In an evolutionary blink of an eye, we have amped up communication from small, intratribal, face-to-face groups to 8 billion people interacting remotely with virtually no common culture. Understandably, our interactions are fraught with misunderstandings and fear.” - SITALWeek #334

We are not helpless in this onslaught despite the proverbial genie being let out. If anything is to change, it will be a bottoms-up effort. It’s probably foolhardy to rely on a top-down approach from these networks. As we discussed, it is not in their interest to simmer things down. When attention is the valuable resource, fights, scapegoating, and rivalries drive profits. Nor is there an easy solution. As Brad said, we are trying to figure out how to co-exist (though Girard would likely argue that there is no co-existing to be had).

What is the way out? Could it be our sameness, the very thing that is posited to lead to our rivalries? By sameness, I mean our shared humanness. It involves more energy expenditure, as it is easier to push others down than raise them up. However, one could argue the larger investment reaps a commensurately bigger reward. Personally, I was not fond of Muslims after 9/11 – more because of fear than any real knowledge. It took me being assigned to work with a Muslim at University that I discovered his humanness. Through that finance class project, we became good friends, bonding over stock market discussions. I attended his wedding in the Middle East and we remain in touch to this day. It might be we must do precisely what we do not want to do – reach across to the “Other”.

We can call out wrongs without denigrating and painting the person as a monstrosity. My hope is we become exhausted with this outrage cycle and move towards more meaningful connections. At some point there will be a backlash. People are seeking connection. The question is if it will be an aberration or the start of the pendulum swinging back.

Perhaps, those that take a different stand can have a disproportionate impact. To use biblical terms, the pinch of salt that flavors the food, the yeast that works its way through the whole dough. As a former short-seller, I don’t have much hope the situation will be reversed. Far too many of us (myself often included) react rather than respond. Like water, we follow the path of least resistance, falling back to our base instincts. Social media platforms merely provide the efficient conduit.